Abstract

Is a “tiny home” for you? Small houses have recently taken the housing market by storm, captured the imagination of alternative housing enthusiasts with its dollhouse façade, sustainable strategies, and quality craftsmanship. It is a trend that is sweeping home improve channels. Generally, between 10 to 40 meters, tiny homes come in diverse types of shapes. As more society moves into the city, living space becomes a precious commodity. The purpose of this essay is to identify the challenges of how talented architects and innovative inhabitants indulged themselves to design small but perfectly formed buildings. Today, minimalist architects have turned in a more focused way to establishing works that might be diminutive in their dimensions, but are definitely big when it comes to trendsetting ideas. They seek a unique concept of creating a home that is just as comfortable as it is functional and aesthetically pleasing. In fact, small houses are no longer synonymous with cheap houses and lack of privilege. Whether in Japanese cities, where large sites are hard to come by or at the frontier between art and architecture, small buildings present many advantages and push their designers to do more with less. Terence Conran said that just because living space is limited in scale, it does not have to limited in style.

Get Help With Your Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional essay writing service is here to help!

This essay argues the motivation of architects behind the tiny house movement that likely revolves around a desire to live modestly while conserving resources through environmental consciousness, the comfort of the inhabitants and the desire of them for a life adventure as inspirations for going small. Thusly, minimalist around the world demonstrates the challenge of the showcase in creative possibilities of compact dimensions.

The research topic analyses carefully thought out, purposeful design of a tiny home to that of a spaceship. Just like NASA is advised by psychologists to understand how the physical space of a shuttle will affect the ethos of astronauts, so should architects work with psychologists to build tiny homes. While the list of characteristics describing tiny house enthusiasts is distinct, the movement has appealed to a surprisingly broad demographic.

Table of Contents

Introduction ....................7

Tiny House Movement

CHAPTER 1 – Context....................9

Minimalism: A Growing Trend

CHAPTER 2 – Context

A Swift Dissection: Japanese minimalist movement grows....................14

CHAPTER 3 – Methodology ....................19

Minimalism and Metabolism Architecture Movements

CHAPTER 4 – Content....................23

Small Eco Homes: Living Green in style....................25

Conclusion

Bibliography....................26

List of figures

Chapter 2

Koichi Torimura, 2014, rhythmdesign [Figure 1] (Interior view of House in Iizuka)

1508 London Studio, 2013. [Figure 2] (Project Elizabeth: The converted Victorian Postal Office)

1508 London Studio, 2012. [Figure 3] (Project Khan: The Kitchen)

Chapter 3

Hiroshi Tanigawa, 2013, MIZUISHI Architect Atelier. [Figure 4] (House in Horinouchi)

ArchDaily, 2011, [Figure 5] (The view into one end of “Lucky Drops by Atelier Tekuto)

Chapter 4

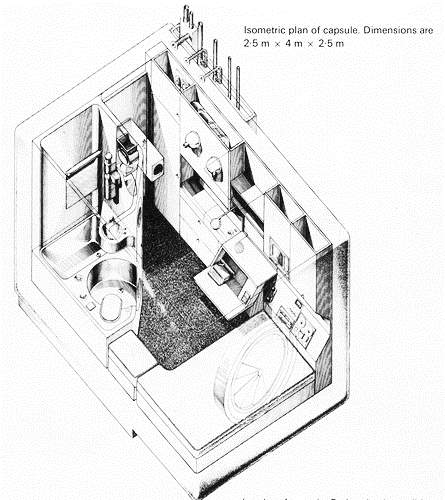

The Asahi Shimbun, 2015. [Figure 6] (Isometric plan of capsule- Nakagin Capsule Tower)

Arcspace, 2014. [Figure 7] (General view of Nakagin Capsule Tower)

[Figure 8] (General view of Small Eco House)

Introduction

Tiny House Movement

Small houses have always had a particular appeal. From the diminutive templates created by the ancient Greeks to the follies of the English romantic landscape, micro works of architecture inspire an enduring fascination that transgresses their function, even if that function is to be a pleasing decoration in landscape. There are a variety of reasons of the love-affair with little forms. Most obviously, the miniaturization of architecture reduces it to a human scale with which we can interact more readily. We are also drawn by the intricacy of their conception and detail and by the fact that smaller buildings usually possess a more tactile quality than constructions of larger scale. The concise purpose of these structures, that they address a single function, simple use or even a purely aesthetic aim, makes them psychologically as well as physically accessible. And yet that is not to say that they are static expressions. (Richardson, Phillis, 2001, XS: Big Ideas, Small Building, pg 2)

New approaches in architecture are usually reflected first in small buildings. The architectural brief of the residential building offers architects an opportunity to realize unusual concepts, to experiment with materials and forms, and to implement new ideas and space. Observers in other countries admire the rigor with which minimalist architects compose these small houses: in his final wooden house, for example, Sou Fujimoto takes up the theme “forest”, which he does not simply understand as an image but tries to embody the material. “Experiments” like these often form the basis for other designs and larger architectural tasks and hence for the evolution of architecture in general.

For centuries architects have used the small form to experiment with space on a reduced scale, to explore the details of construction, the joy of materials and play of form. Although the design of even a modest house contains programmatic complexities, architects trying to achieve simplicity and unity of form and function find themselves faced with the ultimate design question, and it is perhaps in the built answers that we can experience the architect’s vision at its most distilled. A superb example of early experimentation in small houses that reflected one of the finest manifestations of the High Renaissance was the early-seventeenth-century tempietto of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome, built by Bramante. However miniature in size, the tempietto reflects a lofty goal: the reconciliation of humanist, pagan and Christian ideals in a single built feat. But despite the care and thought that little house embody, they are often overlooked or taken for granted in today’s ever more urbanized, global culture.

In an urban context, small houses and functional structures are dwarfed by monumental civic architecture and the focus on function can take precedence over beauty. It may be easier to appreciate miniature homes in the tranquility of the landscape, where function is perhaps less important and contemplation is more readily induced, but either way, the small structure struggles to establish its significance against a backdrop of increasingly grand architectural gestures. The small house architects predominantly induce their ideas in creating a series of themes within a small but infinitely elastic framework. One of the oldest and perhaps most seemingly contradictory objectives for building is to facilitate spiritual or religious contemplation. The tiny homes demonstrates the use of lightweight materials and the pursuit of the self-contained, independent structure, evidence of the influence and rewards of such experimentation in design on a reduced scale. (Richardson, Phillis, 2001, XS: Big Ideas, Small Building, pg 4)

Chapter one - Minimalism: A Growing Trend

A tiny scrap of land might not catch our attention. The minimalist trend is not about destitution, yet it is about accomplishing beauty with less. Minimalist design denies the unnecessary ornate detailing, rather than allowing function to dictate its form. The layers are stripped back, portraying a profound sense of clarity and calmness. Minimalism is not a style, it is an attitude, a way of being. It is a fundamental reaction against noise, visual noise, disorder, vulgarity. Minimalism is the pursuit of the essence of things, not the appearance. It is the persistent search of purity, as an expression of uncontaminated being, the search of serenity, for silence as a presence, for the thickness of spaces, for space as immensity (Claudio Silvestrin, Birkhauser, 1994, pg. 226). The minimal design rediscovers the value in construction materials such as concrete, glass, steel, as the components are left exposed in interiors. When there is less things to distract the eye, each piece of furniture or materials has space to breathe, thusly, stands out in the compacted space. The focus alters the ambience of a room and the rare components that remained its colour, shape and texture. It refines an invigorating escape from the chaotic overstimulation of our everyday lives.

‘Too small to live in and too large to hang on a watch chain’ (said of Chiswick House, London).

Minimalism is beyond time- it is timeless, it is noble and simple materials, it is the stillness of perfection, it has to be being itself, uncovered by useless crusts, not naked but completely defined by itself, by its being. The design opportune to raw industrial aesthetic, as evidence in the refine layout of 1508 London’s award-winning Project Elizabeth (fig.2). The absence of excessive detailing and ornaments emphasized on the clean palette of high quality materials, spawn a splendid backdrop against to feature the art collection for the client. In contrast, minimalist interiors outlines a simplicity of form, colour, detailing and choice of materials. It seeks to eliminate the distraction of awkward proportions and the constant irritation of the catch that does not function unobtrusively. In its place he offers the comfort of exactness of small things done well. For Pawson, architectural reduction is a process that takes you through a mirror. You pass through a point at which a room is merely empty, and emerge out on the other side, in the mirror would to discover richness in the subtle differences between five shades of white, and the sense of release that comes from allowing a wall to flow in space unencumbered by visual distractions (John Pawson- Editorial Gustavo Gill, 1999, SA pg 11).

Right from the start, Pawson has attempted an architecture whose power comes from exploring fundamental problems of space, proportion, light and materials, rather than allowing himself to be side tracked by stylistic mannerisms. In this understated kitchen in Project Khan (fig.3), the modernized flat-panel cabinetry and neutral colour palette retains the visual and sound to a minimum, creating a soothing ambience around the space. What is generally recognized is that ‘emptiness’ in architecture – or empty space – is not empty, but full: yet to realize this fullness requires the most exacting standards and discipline from the architect. Here, there can be no room for uncertainty, or anxious ‘artistic’ effects. Either the worst must be perfect, or not at all. Architecture is ‘frozen music’: the more you reduce, the more perfect its notes must be (John Pawson- Editorial Gustavo Gill, 1992, SA pg 9).

‘Less is more’ by Robert Browning in his poem Andrea del Sarto, was idealized by the architect Mies van der Rohe in the 1940s has become one of the fundamental principles of minimalist architecture, encapsulating the idea of achieving an exceptional design through simplicity. So much more than ultra-modern white-box sterility, a skilfully executed minimalist interior will convey a sense of uncluttered elegance and serenity. Editing a space down to its bare essentials requires restraint and discipline, but the payoff is an interior that is balanced and beautiful. (The Epistle, 18.1.2016). Minimalist John Pawson, awarded for his minimalist aesthetic design quoted ‘the excitement of empty space’. Pawson’s architecture is in this sense a cerebral one. Its restraint appears to deny the richer architectural flavours. But that is not to say that he eschews the physical qualities of design. Unlike those architects whose work is intellectually driven to the exclusion of all else, to the extent that it amounts to the cartoonlike realization of the proposition which entirely lacks the sensual and spatial qualities of architecture, Pawson has always managed to synthesize the two strands (John Pawson- Editorial Gustavo Gill, 1992, SA pg 14).

Figure 1 – TRAVEL; Interior view of House in Iizuka by rhythmdesign

“In Japan, there’s a saying (‘tatte hanjo nete ichijo’) that you don’t need more than half a tatami mat to stand and a full mat to sleep,” says Yamashita. “The idea comes from Zen — and a belief that we don’t need more than the fundamentals.”

Traditional Japanese design and Zen philosophy are distinct influencers of minimalist aesthetic. Straightforward, curtail lines, the rejection of disarray, common materials and an emphasis on living ‘authentically’ are all sturdily appreciated. The Japanese minimalist architect Tadao Ando, while thoroughly contemporary in style, he is deeply rooted in Japanese culture and religion. The late 19th century Arts and Crafts movement, exposes a guiding principle of ‘truth to materials’, and the 1920s Bauhaus of which Mies van der Rohe was the last director can be considered as the pioneer predecessors of modern minimalism, which then emerged during the 1960s.

Minimal architecture is, as far as I am concerned, first of all an attitude to life; including the most mundane things: from ethical behaviour to choosing a toilet roll. Most of you, however, want to be, or claim to be, architects, and what you most like to hear about are buildings per se, therefore missing the point. We must learn how to see, how to read and how to think. (Claudio Silvestrin, Birkhauser, 1994, pg 212). The most stunning piece of minimal architecture would be rather meaningless unless visual tension is vanquished – calm and serenity are a must: spirit and matter must be in balance. Our modern perception reduces all things- including mental things – to quantifiable material entities, thus negating the spiritual of life.

Figure 2 – Project Elizabeth: The converted Victorian Postal Office

Figure 3 – Project Khan: The Kitchen

Chapter two - A Swift Dissection: Japanese Minimalist Movement Grows

In state-of-the-art, architecture was predestined for the masses, for the communal. Blocks of buildings were designed and constructed instantaneously and economically with the same appearance and materials. Society are seeking for own regions and local traditions for inspirations. We live in the era of globalization where everyone wants the same thing. The demand for small homes in Japan results partly from land scarcity, property prices ad taxes, as well as the impending danger posed by the country’s regular earthquakes and typhoons. That is where design is moving – people simply prefer smaller homes and seeking a minimalist lifestyle. Rising population mean cities are overcrowded, for example in Japan, there are 1.9 million of one to two person households, with a housing supply of 1 million one bedroom apartments, resulting in a shortage. The solution comes back to Tiny Homes and is the reason for its modern revitalization. People from all over the world wants to live in Tokyo city, thus architects thrives to develop scalable housing that is safe, affordable and innovative to meet client needs.

For no matter how small the room, providing your eye could travel freely around it, the space it contained was limitless. He was repeating, in effect, the premise underlying medieval monasticism that the monk, who sat in his cell, was free to travel everywhere. Here, at last, I felt, was someone who understood that a room – any room, anywhere – should be a space in which to dream. It was a real thing: a room with ‘wabi’. I walked around the walls, watching its places, shadows and proportions in a state of near-elation. To his friendship with the architect, Shiro Kuramata, he owes the insight that you can make the most daring experiments with new materials and new technology without having to sacrifice the spirit of ‘poverty’. (John Pawson- Editorial Gustavo Gill, SA, 1994, pg 12). Traditional Japanese design with its clean forms and simplicity was a predecessor of minimalism. The theory was influenced by the spare aesthetic of Japan’s traditional Zen Buddhism from the reflection of Japanese culture where inspiration came from the United States.

‘In the western architectural tradition. A building is primarily framed by means of walls and windows. On the other hand, in the traditional Japanese architecture, horizontal planes (That is, the floor and the ceiling) are the dominant framing devices’ quoted by Kengo Kuma

The creativity of Japanese architects is acknowledge by the design of the buildings and capability of creating possibilities through tiny spaces. The minimalist architects plays the boundary of spaces, exploit unusual materials and cultivate new concepts for living together. The short life of residential buildings has driven to a colossal collection of architectural ideas and tiny houses documents the approaches. Japanese residential buildings are to be known as seismograph of current trends in architecture. “If you tried to build a normal house on a super-small plot of land, it would end up being really cramped. So in order to make the house as roomy as possible, we have to think up new structures and assembly,” quoted by Yamashita.

Compared to European architects, Japanese architects have a somewhat easier time realizing their visions as residential buildings. First, there are hardly any design guidelines; second, Japanese clients who hire an architect know exactly what they are getting into. They want special houses that stand out from the brown and green masses; hence they are prepared to accept that the architecture will not function exclusively as a subordinate shell but will at time even demand a symbiosis, an adaption of living habits. This different way of thinking about sustainability in Japan can, of course, be regarded critically as well, but anyone who looks at the effective use of energy in Japanese tiny homes cannot demonize it entirely. The greater tolerance of their clients – with regard to sacrifices of comfort, for example – means more design freedom for architects. The small houses simply can be adapted to the changing living conditions and hence can be seen as the liveliest and most spontaneous element in the urban fabric.

“Asymmetrical pieces of land can often be obtained cheaper than others. And it is an architect’s job to work with the land and fulfil the client’s request,” says Yamashita. But in recent years, Japanese minimalist architects have turned inevitability into an asset, striving to design unorthodox and visually spectacular tiny homes on remarkably congested land by redefining the rules of designing Japan’s dwellings. Miniature homes conserve space by eliminating conventional elements like hallways, entranceways, closets and inner walls. Architects indulge in ordinary vision by idealizing asymmetrical walls, translucent facades, and cantilevered floors to exploit natural lightings. Windows, were prefabricated in various shapes and sizes, concealed near the base and scattered across walls and façade of the building as openings. Furniture are specially made and can be folded into the wall, allowing more space in a room. A bathroom can be separated by having a glass partition or curtain. Sightlines that extend the length of the house, focusing on the spaces that borrow from adjacent spaces.

Figure 4 – House in Horinouchi, Tokyo by Mizuishi Architect Atelier

Japanese architect Yamashita built a cathedral-like futuristic and long home on a 40 feet wide sliver land – a house in downtown Tokyo – and named the small house “Lucky-Drops” (fig.5). The land was a leftover scrap and it was less expensive due to its irregular trapezoid shape. He had to be creative, but it was an astonishing result. There’s a saying in Japanese, the last drop of wine is considered to be lucky, as an inspiration. The skinny home was built on an extreme narrow space as light could only penetrate from the ceiling. “All the light comes in from the top. So the whole house becomes like a Japanese paper lantern” says Yamashita. The significant rise in quirky tiny homes was driven with new technological design and materials, has caused the price of custom-built house slashed as much as two-thirds, making these houses affordable for single and middle class inhabitants.

For example, Minoru and Aki Ota, a young Japanese couple, reside in a tiny home that spans less than 45 square meters. The interiors and kitchen table were made entirely of precast concrete. “We weren’t interested in a big house in the suburbs. It’s not that we wanted to live in a micro-house, but it turned out to be plenty of room for two and convenient, “Minoru Ota says. The tiny home features narrow openings at ground floor that was strategically placed to reveal bits of outdoor scenery and a glimpse of natural lighting. The concrete made furnishings made the house to be warmer and comfortable, they said it was like living in an art museum. “Where the forms of these houses is very unusual, asymmetric, seemingly unbalanced or lopsided, it’s because there’s a room or certain functions that need to be accommodated, and rather than make everything be symmetrical and line up, they just said, Well, if this living room is just going to have to stick out, over the parking space, so be it.” Brown says, author of The Very Small Home: Japanese Ideas for Living Well in Limited Space.

“People tend to think of homes simply in terms of floor space. We architects think in 3-D,” Yamashita says. “Using all three dimensions, we can make a space look larger, and more functional. It becomes easier to devise ways of bringing in more light and air.” The tiny house can be built higher to create more space, as if making the house feel like it is extending upwards into the sky, with high ceilings to avoid compactness of the house. “It’s kind of a psychological jujitsu,” Brown says. The design changes the sense of perception towards things that makes you feel claustrophobic, rather than focusing on life or people that you are living with. The techniques in Japan architecture exemplify the comfortably house residents in other teeming cities.

“We are larger people physically than the Japanese, we do tend to need more space, we’re less comfortable in some sitting positions, like sitting on the floor, than most Japanese are. But I think we could also accommodate ourselves to it,” Brown says.

In conjunction, Japanese minimalist who have modernized their small house design based on traditions such as the teahouse, they have not accommodated to miniature home but now they revel in them.

Figure 5 – The view into one end of “Lucky Drops by Atelier Tekuto

Chapter three - Minimalism and Metabolism Architecture Movements

Minimal architecture is, first of all an attitude to life; including the mundane things: from ethical behaviour to choosing a toilet roll. Most of you, however, want to be, claim to be, architects, and what you most like to hear about are building per se, therefore missing the point. The modern architects – Van der Rohe, Barragan, Ando, Kahn, and Van der Laan – have all paid attention to some of the ancient principles which may cautiously be called classical. Mies, who is perhaps the master of our century, has been, a source of inspiration. His abundant use of clear glass, however- later stretched ad nauseam by other architects-reduced sunlight to a mere bulb; nothing but a crude function.

“The feeling of one’s own being (beings and being in general) is intensified to its full potency once the thickness of the space surrounding one’s own body manifests itself. Thus the ideal construction opens up the seeing of such thickness by erecting unadorned walls to form pure mass of air, uncluttered and unconquered, free from the arrogant presence of man’s self-assertive will. Only through this ‘clearing’ is space rendered visible. Quoted by Claudio Silvestrin (Birkhauser- Publishers for architecture pg 7)”

Mies’ ‘Less is more’ is open to many interpretations. It has been used as the first principle of minimalism; it has been deconstructed with syllogisms such as ‘more is less’. But one thing is certain: the final goal is ‘more’. And here lies the tragedy of modernity – a philosophic dualism which inevitably sees one element opposite and in conflict with its complement. (i.e. More versus Less; and Function versus Form). The modernist movement, with Fuller at its head, strongly believes that technology is the cure for society – a tragic belief. Technology, consumerism, material possession, and the search for more and more things with which to clutter up our planet and our rooms, the will for more and more things to accumulate or experience, have reduced our sight to mere optics that we can no longer see. (Claudio Silvestrin, Birkhauser, pg 213).

Kurokawa first came into the public eye in 1960 when, along with other architects, he founded metabolism, an architectural movement and philosophy of change. Kisho Kurokawa and the other architects, was in their early thirties. They had studied the politics of European avant-garde movements and were determined to fashion an ‘ism’ which would compete with those in the West. Metabolism became an extended orthodox modern architecture. It compared buildings and cities to an energy process found in all life: the cycles of change, the constant renewal and destruction of organic tissue. But as Kurokawa said regarding Buddhism and change, ‘I can be Buddha, but you can’t be Christ. What he had in mid was the infinite transformation prophesied in his philosophy, the belief that one is reincarnated in every age, perhaps as a plant the first time, or an ‘enlightened one’ (a Buddha), the next.

Find Out How UKEssays.com Can Help You!

Our academic experts are ready and waiting to assist with any writing project you may have. From simple essay plans, through to full dissertations, you can guarantee we have a service perfectly matched to your needs.

View our academic writing services

Kurokawa is often referred to as the ‘capsule architect’, a characterization he both encourages by polemic and deplores. ‘Capsule architecture’ developed from his own Metabolist researches in prefabrication done in the late fifties, which culminated in a project for a giant block which could incorporate standard elements; basically five equal elements put together like a meccano set. The elements and image, while mass-produced, were actually based on traditional models of the farmhouse and tatami mat. It was a typical product of modern Japanese design having all the ambiguity of the figure-ground illusion: looked at one way it seemed totally futurist, from another angle totally traditional. It is present in the Nakagin Capsule Tower (fig.7), his most famous capsule building to date, finished in Tokyo in 1972. Here again the tatami proportions of the room (roughly 4 by 25 metres) exist antagonistically with the hardware of a totally self-sufficient space capsule. All the furniture is built in- the bedside control console, the stereo tape-deck and calculators- and yet the tiny space and proportions are the conventional ones. Yet here again Kurokawa is being traditional when we think he is most futurist. Tea pavilions always have to be asymmetrical and unfinished, to let the imagination complete the work. (Charles Jencks, Kisho Kurokawa, 1977)

Nakagin is not an apartment house. It was intended to provide single bedroom dwellings in the heart of Tokyo, studios for the use of businessmen living in distant suburbs of the city, or hotel space for businessman staying in Tokyo for brief periods. Throughout the decade before this was built, the population of Japan’s metropolises had been declining and in central city areas the majority of buildings are office buildings and other types of commercial architecture. The number of homes rapidly decreased, as large numbers of people moved to outlying areas. It became an issue of some importance to restore housing units to the central part of the city. This building was intended as one tactical move to provide studios, an extra bedroom or place for social activities. If individual capsules are given specialized functions such as living room, bedroom, kitchen, and so on, and linked by access doors, they may be used as on ordinary dwelling. (fig.6)

The concept of metabolism is nothing but a sense of impermanence. To Kurokawa, what makes up this universe is a multitude of selves called jiga. Kurokawa calls it capsule. The world is then a juxtaposition of free walls, coexisting sometimes in harmony and sometimes in conflict through en. His notion of the capsule is not one of parts; it is a self-sufficient component like living cell, a functioning entity, a meaningful space unit with its own life cycle. It lives and dies, but the en is always there to take on new cells. The champion of these ‘Metabolist’ architects in contemporary Japan is Kisho Kurokawa. (Architecture Plus, January 1974)

Figure 6 – Isometric plan of capsule- Nakagin Capsule Tower

Capsule architecture springs from the thought expressed in Homo movens, published in 1969. The Japanese concept of housing is formed by the large amount of travel, and people who had homes in agricultural villages and worked in the cities considered their residences away from the village as temporary abodes. For modern man in our highly mobile society – for Homo movens – the capsule dwelling will probably come to be of high importance. (Charles Jencks, Kisho Kurokawa, 1977)

Figure 7 – General view of Nakagin Capsule Tower

Figure 7 – General view of Nakagin Capsule Tower

Chapter four - Small Eco Homes: Living Green in style

Fresh perspective on modern design that is stylist yet ecologically sound living spaces that is idealized by architects in these small-scale homes. The challenge of limited spaces in this environmentally sensitive and small scale residential design, keeps the modern day architects, innovative designers, building craftsman and homeowners aware with the environmental consciousness that results in designing eco-friendly living spaces with small carbon footprints that are built with sustainable materials. The inspiration of the design proves that small-scale efficiency and thoughtful design can overcome the apparent restrictions of small setting.

The Small Eco Homes display various features of modernized eco design that demonstrates the environmental and economically benefits. The architects should be aware about the important details involved in the building, such as regional planning, climate regulation and drainage systems and the factors to be considered during selection of materials: the total consumption of energy used in manufacturing the end-product, whether the material used is durable and it is recyclable or safely disposable when it is broken down.

Environmental impact is a growing concern, thus it challenges and antagonize the designer and the solution due to it ecological sensitivity. The designers would create colour schemes to enhance the feeling to openness to the environment, indulge with high ceilings to make multiple levels and sliding doors or openings to maximize the open space, even installed collapsible furniture to resolve the design in the compact space. The design results and can be transformed into a comfortable, modern and environmental sensitive habitat. Also, reveals the parameters of ecological design that have expanded in few years’ time. Relating to the concern for the environmental with aesthetic sensibility, it is essential that the architects and designers should outsource their interest in creating warm and inviting homes that is not only aesthetically to inhabit. But help to conserve and protect the natural environment.

Whether intended to block out urban clatter or to commune with the natural environment, the small eco homes that mediate nature and the appreciation of that natural world through their walls and roofs take a variety of forms; bunkers that bury themselves in the earth, perfectly positioned panoramic lookouts that take in an untouched rural setting. The aim of this isolation is manifold; to observe, to contemplate and to become inspired and calm.

Architects who demonstrate a reverence for the landscape, and sensitivity to their impact on their surroundings are heartening in time of serious ecological concerns. The challenges for designers and architects with such an awareness are several: how to create environmentally and visually friendly small homes and how to respond to the sweeping drama of a landscape or an untrimmed wilderness in a manner that enhances nature and our experience of it. In view of this complex relationship, it is not surprising that small shelters in the landscape have a somewhat mythical history. Perhaps it is because man feels dwarfed by the grandeur of the natural world that we find ‘humanized’ scale exemplified by the projects presented here so appealing. Concerned with leaving the smallest footprint, these designs aspire toward the compact to heighten the perception of the surroundings, particularly the presence of water, which always provides a sense of limitlessness and grandiosity.

Figure 8 – General view of Small Eco House

Conclusion

“Architecture from now on will increasingly take on the character of equipment. This new elaborate device is not a ‘facility’, like a tool, but is a part to be integrated into a life pattern and has, in itself, an objective existence” (Charles Jencks, Kisho Kurokawa, 1977)

The courage to experiment when designing small houses, the architects, designers and innovative inhabitants play with the limits of space, employ unusual materials, and develop new concepts for living together. The design of small houses reveals the creativity of the architects as well as their ability to organize even the tiniest space over the years. The short lifespan of residential building has resulted in an enormous store of architecture, and this is the new approach to Tiny House Movement that modern minimalist should be aware of. For the architects, small residence for private clients have been the only opportunity thus far to realize their design ideas. The building of small houses gives them a chance to become known and to be perceived internationally as well. It is important to note that the new breed of leading architects is predisposed to face the changing world with a broad-minded, all embracing attitude, which may not allow them to control the basics which can then shape their physical environment.

Japanese small houses, for instance, have always been a seismograph of current trends in the country’s architecture. The focus is on the architectural concept conveyed through numerous ideas to create an economically and comfortable compact homes for the inhabitants. The miniature homes makes the architects momentarily pause to ponder their meaning, or simply to appreciate the elegance of their creation. From the spectrum of functions and styles of these structures, it is clear that size imposes no limits on creativity, and utility is no constraint to beauty. Thinking small is a wonderfully constructive exercise.

Small House designers seek new ways of creating a home that is just as comfortable as it is functional and aesthetically pleasing for the habitants. By implementing thoughtful application of green living principles for the small eco homes, focus on renewable resources for construction and cleaver ingenuity, the concept of living in small spaces exemplify sustainable living at its best.

Bibliography

Books and Contribution to Books

Introduction

Richardson, Phillis, 2001, XS: Big Ideas, Small Buildings.

TASCHEN, 2017, 100 Small Buildings (Bibliotheca Universalis)

Chapter 1

Silvesterin, Claudio, 1999, Franco Bertoni Essay: Cladio Silvesterin

Gili, Gustavo, 1992, John Pawson: Pawson Monograph

Kahn, Lloyd, 2012, Tiny Homes: Simple Shelter

Gestalten, 2017, Small Homes, Grand Living: Interior Design for Compact Spaces

Richardson, Phyllis, 2011, Nano House: Innovations for Small Dwellings

Morrison, Andrew, 2017, Tiny House Designing, Building, & Living

Chapter 2

Hildner, Claudia, 2011, Small Houses: Contemporary Japanese Dwellings

Brown, Azby, 2012, the Very Small Home: Japanese Ideas for Living Well in Limited Space

DH Publishing, 2008, Small House Tokyo: How the Japanese Live Well in Small Spaces

Gili, Gustavo, 1992, John Pawson: Pawson Monograph

HIRAI, Kiyoshi, 1998, The Japanese House Then and Now: Tokyo

Casa Brutus, 2008, special issue “Traditional Japanese Architecture and Design” (part 1)

Chapter 3

Bertoni, Franco, 2002, Minimalist Architecture

Bletter, Rosemarie, 1996, Adolf Behne: The modern Functional Building

Maddex, Diane, 2003, Wright-Sized Houses: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Solutions for Making Small Houses Feel Big

Chris van Uffelen, 2014, Extreme Minimalism: Architecture

Cerver, Francisco Asensio and Francisco Asensio Cerver, 1998, The Architecture of Minimalism.

ERNST& SOHN, Academic Editions, 1991, Kisho Kurokawa; The philosophy of symbiosis

Haris, John, 1981, Kisho Kurokawa

Jencks, Charles, 1977, Kishop Kurokawa: Metabolism in Architecture

Zimmerman, Claire, 2006, Mies Van Der Rohe: Less is More – Finding Perfection in Purity

Chapter 4

Gutierrez, Manel, 2015, New Eco Homes: New Ideas for Sustainable Living Hardcover

Mola, Francesc, 2010, Small Eco Houses: Living Green in Style Paperback

Zeiger, Mimi, 2009, Tiny Houses

Richardson, Phyllis, 2011, Nano House: Innovations for Small Dwellings

Richardson, Phillis, 2001, XS: Big Ideas, Small Buildings.

Journal Article available from the internet

Ivanoff, Ada, 2014. Design Minimalism: What, Why & How. Available at <https://www.sitepoint.com/what-is-minimalism/> [Accessed on June 06, 2014]

Lim, Megumi, 2016. Less is more as Japanese minimalist movement grows Available at <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-japan-minimalism/less-is-more-as-japanese-minimalist-movement-grows-idUSKCN0Z50VP> [Accessed on June 19, 2016]

Craft, Lucy, 2010. In Japan, Living Large In Really Tiny Houses Available at <https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=128953596> [Accessed on August 3, 2010]

Atelier Tekuto, Toshihiro Sobajima, 2017, The secrets behind Japan’s coolest micro homes Available at [Accessed on 6th February 2017]

Ashcraft, Brian, 2013, Cramped or Not, I Want To Live in These Tiny Japanese Houses Available at <https://kotaku.com/cramped-or-not-i-want-to-live-in-these-tiny-japanese-h-1051646360> [Accessed on 8th July 2013]

Makoto Yoshida, 2017, Tight squeeze: The secrets behind Japan’s coolest micro homes Available at < http://edition.cnn.com/style/article/japan-micro-homes/index.html [Accessed on 6th February 2017]

Online Resources

Minimalism: The Epistle <http://1508london.com/epistle/minimalism-a-growing-trend/>

Saving space: Big Ideas for small building –TASCHEN <https://www.taschen.com/pages/en/catalogue/architecture/all/49323/facts.small_architecture.htm>

Social Housing Design- Japan’s Micro-apartment <https://socialhousingdesign.wordpress.com/2015/03/18/the-microapartment/>

The Poetry of Light: 10 Quotes on Minimalism by Tadao Ando <https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/industry/10-quotes-on-minimalism-by-tadao-ando/>

Live Large In The Really Small Houses Of Japan

Small Houses: Contemporary Japanese Dwellings

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: