Alternative Approaches to Improving Literacy

Introduction

Literacy is one of the most significant components of a child’s early educational experience. If a student is not reading proficiently by third grade, they are subject to retention, difficulty meeting curriculum standards, and struggles keeping up in classes from then on. In fact, research shows that students not proficient by this time are over four times more likely to drop out of high school than their proficient peers (Neuman & Knapcyzk, 2018). There are a variety of perspectives on the issues surrounding literacy, and these perspectives can be used to frame the issues and possible interventions in numerous ways. While many interventions have found some success, there is still great debate about what the ideal solution is to adequately address literacy rates in this country. Children in higher-income families tend to experience conditions conducive to learning, including good nutrition and secure housing (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2018). They also have more access to resources, like books, quality preschools, and tutors as well as the resources to support students’ learning during the summer when students are susceptible to losing knowledge and skills gained over the previous school year.

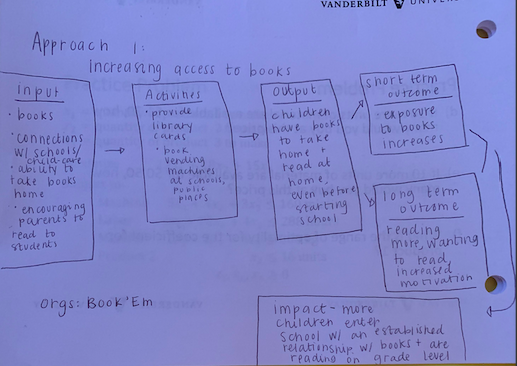

Approach One

The first conceptual approach to improving literacy rates in the Nashville area is increasing overall access to books for all students, particularly low-income students. Sixty-one percent of low-income families do not have access to books, which puts children at a disadvantage both socially and academically. The immense disparities between high and low-income communities’ resources available in homes and child-care sites is disconcerting. Researchers estimate that a student from a high-income family will enter first grade with approximately 1,000 hours of being read to, compared to 25 hours for a low-income student (Nurmi et al, 2013). 82% of fourth-graders from low-income families are not proficient in reading (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2018). Research also shows that increasing low-income students’ access to books, thus giving them the freedom to choose what they want to read improves academic performance and motivation to read and learn (Williams,, 2017). Providing access to books before children start school could possibly reduce achievement gaps between low-income students and their affluent peers. A local organization that supports this mission is Book’em. The organization’s mission is to, “ create a more literate Nashville by helping economically disadvantaged children, from birth through high school, discover the joy and value of reading through book ownership and enthusiastic volunteers.” (Book’em.org, 2018)

Get Help With Your Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional essay writing service is here to help!

This approach would involve flooding classrooms (and other areas children frequent) with illustrated storybooks and training teachers to ensure students interact with books frequently and effectively (Neuman & Knapcyzk, 2018). This would not stop at the classroom, and would include book drives that allowed students to take books home, access to library cards, and possibly receiving books at doctors’ offices. Immersion through text leaves students highly motivated and prepared to engage in various communicative activities. According to proponents of attempting this approach, the literacy rate in this country reflects the perpetuation of the achievement gap between high-income and low-income students. High-income students consistently perform better than low-income students in all subjects, especially reading and writing, and the current gap remains unchanged despite efforts to improve it. It is widely documented that children enter school with varying levels of school readiness skills and that, in many cases, it is the discrepancy between these skill-sets at school entry that lay the foundation for the differences in academic performance over time.

The problem is that students from low-income communities are not exposed to books much outside of school, and when they are in school, the books they see are low quality, difficult to understand, and unexciting. This leads to a lack of interest in books and reading, which is the foundation for a quality education. This, in comparison with the experience many high-income students have with books, like being read to by their parents from a young age, freedom to choose what books they read, and a previously established relationship with books and reading, foster conspicuously lower literacy rates in certain children (O’Connor, 1999). Actual programs like this one have been implemented in many urban communities in the past. The results vary. In some communities, making books easily accessible has increased students motivation and reading performance, but in others, increasing proximity to books did not have the same effect (Neuman & Knapczyk, 2018). In some instances, access to high-quality books has been shown to lead to improved reading skills, where students are reading longer and with increasing difficulty, and an improved attitude towards reading. Many parents agree that these resources provided the necessary support to incite their children’s interest in books and reading skills. With this, researchers noticed that the same people were exploiting their newfound access to books, while many others still did not take advantage. According to experiments conducted by Neuman and Knapcyzk (2018), 40% of people chose not to engage with books, citing a lack of interest in reading. This phenomenon reflects the idea that physical proximity to books may not be enough. There is also a need for adults around children to exhibit an interest in books so that they can build that social connection.

The logic model reflects the exemplary, ideal model for this approach. While the linkages used in the logic model are possible, and have happened in the past, they are not the case 100% of the time. Ideally, increasing the flow of books and students’ exposure to books through various avenues and providing access to library cards would lead to an output of children having the ability to take more books home, and thus as their exposure to books increases, so would their motivation to read them and grow their literacy skills. Long term, the impact of this would be that students are more prepared to achieve expected reading goals for their particular grade levels, and the rate of students falling behind would decrease. These links make a lot of sense, but due to factors outside of the ones addressed by this approach, it is not guaranteed that this approach will be effective. Organizations like Book’em seek to provide that access to low-income students across Nashville by distributing books to individuals, programs, and schools, and they are effective to a certain extent. Still, though, many children are not able to receive books through programs like these.

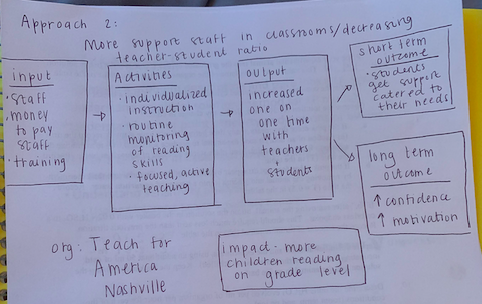

Approach Two

The second conceptual approach to improving literacy rates in Nashville is to increase the number of teaching assistants in classrooms. Nurmi et al (2013) note that when there are an increased number of support staff in a classroom, teachers are more likely to base their instruction on the particular students’ needs. With less pressure on the teacher by reducing teacher-student ratios, teachers are more able to cater to a students’ particular skills, thus meeting them where they are. According to proponents of this approach, the problem causing lower literacy rates among some students is that teachers are not able to provide them the educational support they need or cater to their specific literacy abilities for a variety of reasons. Those include large class sizes, lack of auxiliary support (like teaching assistants), and lack of experience. This leads to many students falling behind and teachers not having the time to work with them individually to remedy these gaps.

In theory, it is sensical to think a teacher or teaching assistant would adapt the methods they use to teach a student based on that students’ literacy skills or overall academic performance. In practice, that design can lead to negative relationships between teachers and students. For example, some studies show that high achieving students receive preferential treatment from teachers, while low achieving students were subject to more criticism and micromanagement (Kelley, 2016). Other studies show that high achieving students receive more emotional support and positive affirmation from their teachers, but low achieving students receive more active instruction and support. Students’ literacy skills at the end of kindergarten are a powerful predictor of whether or not a teacher was able to give a student individual reading support (Nurmi et al, 2013). For example, if a student was found to be performing below standards at the end of kindergarten, their first grade teacher would be more likely to give them and their reading skills extra attention. Overall, most research shows that individualizing reading instruction according to students’ skills seems to improve students’ reading development during their early educational years.

The logic model is, again, the idealistic blueprint of implementing this approach. According to this model, increasing staff in the form of teachers and teaching assistants, as well as providing more training and supplies for them would lead to more one on one time between instructors and students. This would translate to a more comprehensive understanding by teachers of students’ reading levels, and the decreased teacher-student ratio would allow the instructor to spend more time engaging the student and allow them to accommodate the student’s individual literacy needs. The output of these things would be that they would facilitate new, innovative approaches for teachers and improvements in the skills they are focusing on with students. Short term, this would help students that are lagging behind remain in line with their peers in terms of academic performance as they are receiving individualized support. Long term, this would remove the need for extra tutoring because students would already be on par with curriculum and state standards. They would also have increased confidence and motivation to read. The impact of this approach would be that more students are reading at the level they should be for their grade level. The linkages in this model make sense, but they do not translate to guaranteed positive results. An organization that aligns with this goal is Teach for America Nashville. This organization seeks to fight educational inequity by recruiting and training teachers to enter low-income schools and cater to needs of students to enhance their growth and  educational experiences.

educational experiences.

Evaluative Comparison

These approaches seek to address the issue of literacy in two distinct ways. They approach the problem from different angles, yet seek to have the same long lasting impact. In terms of the first approach, the problem definition implies that if students from low-income communities had the same access to books and were building the same relationships with books early-on as those from high-income families, they would also be reading on the same level with these students. From this problem definition, you would assume that giving low-income students the ability to have books and a choice in the books they read would level the playing field when comparing them to their high-income counterparts. The transition from one step to the next in the logic model makes sense. If you increase access to books and get students reading more, that will aid in improving their overall literacy. But at the same time, just because one has the ability to have books and read them, this does not necessarily guarantee they will. As was previously mentioned, the logic model reflects an idealistic approach (Frumkin, 2010). This approach is a means of providing books to those that do not have access to them, thus fulfilling a need in the community as opposed to serving as a preventative measure. It is more of an individual level measure, as it works on a person to person basis. If one student takes advantage of the access to books and their literacy improves, this does not guarantee that the next will, too. It is also more ameliorative than transformative. It seeks to improve literacy rates, not shift the entire education system, or fix the entire achievement gap.

Find Out How UKEssays.com Can Help You!

Our academic experts are ready and waiting to assist with any writing project you may have. From simple essay plans, through to full dissertations, you can guarantee we have a service perfectly matched to your needs.

View our academic writing services

The second problem definition also implies that there are clear solutions. From this definition you can assume that the solution to this issue is to hire more teachers, add more teaching assistants, and reduce the teacher-student ratio so that teachers are able to focus more on individual students as opposed to their classes as a whole. The logic model makes sense in theory and when you are thinking optimistically, but in reality there are a few holes in it. For example, if you add more teachers and more training, this does not guarantee teachers are going to use these decreased ratios to focus on students with identified needs. It also does not guarantee that if they do focus on such students, that the individualized attention will be impactful. If a teacher does not know how to work with a particular student, the extra time spent does not necessarily equate to improvements. Increased one on one time also does not mean the student will automatically be motivated to engage, or their confidence will increase. This approach is more of an organizational level change (Frumkin, 2010). If you increase the amount of teachers, this could be done on a district, state, or national scale. Typically such changes happen at a district level, meaning all schools in a district needing more teachers would receive them. This approach seeks to prevent students from falling behind and to ensure they are on grade level at all times up until and after third grade. It definitely seeks ameliorative change. It seeks to improve a problem that we currently have, but prevent the problem from persisting in future.

There are many similarities between these approaches, but comparatively speaking the second approach of increasing teacher support in the classroom seems to be more reliable. They were both designed using the theory of change model in which you determine your long term goal prior to an intervention. While increasing access to books is a great thing, I am not convinced it does enough to completely level the playing field or alleviate the problem that already exists. Teachers catering to students and their needs leaves room for a lot more interpretation. Generally speaking, addressing issues in individualized manners tends to be more effective because with increased information comes the ability to ensure solutions work for the intended person. The evidence supports increasing access to books, but it is lacking in providing causal evidence that this is what improves literacy. It could be that this helps, but in conjunction with other factors. The literature does not discuss this possibility. There is a clear relationship between individualized, active instruction and improved literacy (O’Connor, 1999). There are many studies that exhibit these same results.

In this class, though, our dollars would likely be better spent attempting to increase access to books. We are working in a limited time frame, and while any money would help, our funds would not go as far in an attempt to hire teachers or introduce training as they would in increasing accessibility. This issue and the conditions of this class reflect a small cube issue, and increasing access is a smaller cube solution (Brest & Harvey, 2018). It can be done on a small scale or a large scale, and our money could go a long way in trying to alleviate this need. The need is near term, but has the potential to become long term, and is a non-life threatening need. Proponents often emphasize how this method of improving literacy is cost effective. Our dollars would likely have higher leverage donating to an organization like Book’em that provides access. There are a plethora of organizations that have engaged in this sort of program, giving us many options and the opportunity to prepare for success as we have a lot of information to use to decide.

References

- T. (2018). What We Do. Retrieved from https://www.teachforamerica.org/what-we-do

- Nurmi, J., Kiuru, N., Lerkkanen, M., Niemi, P., Poikkeus, A., Ahonen, T., . . . Lyyra, A. (2013). Teachers adapt their instruction in reading according to individual childrens literacy skills. Learning and Individual Differences,23, 72-79.

- Home. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.aecf.org/

- O’Connor, R. E. (1999). Teachers Learning Ladders to Literacy. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice,14(4), 203-214.

- Kelley, J. P. (2016, September 04). Schools use team approach to boost all kids. Retrieved from https://www.daytondailynews.com/news/schools-use-team-approach-boost-all-kids/pZm17AyktjUqMroiNpx1MI/

- Socioeconomic Factors and Literacy: How Access to Books Matters. (2016, August 29). Retrieved from https://rxreading.org/research-on-literacy/socioeconomic-factors-and-literacy-how-access-to-books-matters/

- Neuman, S. B., & Knapczyk, J. J. (2018). Reaching Families Where They Are: Examining an Innovative Book Distribution Program. Urban Education,004208591877072.

- Home. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://bookem-kids.org/

- Williams, A. (2017). Access to Reading. The Social Life of Books.

- Proximity to Books Enhances Children’s Learning. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/2018-05-03/proximity-to-books-enhances-childrens-learning

- Brest, P., & Harvey, H. (2018). Money well spent: A strategic plan for smart philanthropy. Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books, an imprint of Stanford University Press.

- Frumkin, P. (2010). The essence of strategic giving: A practical guide for donors and fundraisers. Chicago and London Univesity of Chicago Press: Univesity of Chicago Press.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: