Are ethical purchases and fast fashion mutually exclusive?

An investigation of denim.

Introduction

In the UK more than 2 tonnes of clothes are bought every minute (Express, 2019) with an estimated £140 million worth of clothing going to landfill each year (WRAP,2019). Given these figures are significantly alarming, a growing consensus of reducing waste results in the question of ‘how can this be reduced?’. In this essay I will investigate whether ethical purchases and fast fashion can be mutually exclusive, meaning whether they can work together to create sustainable fast fashion. But what do these two terms mean? The definition of fast fashion, according to Lexico, is ‘inexpensive clothing produced rapidly by mass-market retailers in response to the latest trends’ and in comparison, the definition of ethical is ‘avoiding activities or organizations that do harm to people or the environment’. From the offset, they would never be compatible as some may say it is the ‘produced rapidly’ which causes fast fashion to create detrimental social and environmental impacts.

In the UK more than 2 tonnes of clothes are bought every minute (Express, 2019) with an estimated £140 million worth of clothing going to landfill each year (WRAP,2019). Given these figures are significantly alarming, a growing consensus of reducing waste results in the question of ‘how can this be reduced?’. In this essay I will investigate whether ethical purchases and fast fashion can be mutually exclusive, meaning whether they can work together to create sustainable fast fashion. But what do these two terms mean? The definition of fast fashion, according to Lexico, is ‘inexpensive clothing produced rapidly by mass-market retailers in response to the latest trends’ and in comparison, the definition of ethical is ‘avoiding activities or organizations that do harm to people or the environment’. From the offset, they would never be compatible as some may say it is the ‘produced rapidly’ which causes fast fashion to create detrimental social and environmental impacts.

I conducted a questionnaire asking 266 females, aged between 14-27 years of age, to gather primary research for both my artefact and this essay. The questionnaire presented 4 statistics as to how much water was used in the production of a pair of jeans, the participants then had to select one of the statistics which they thought was right. Overall, only 32% of the participants selected the right answer which was 7,000-11,000 litres. This shows the lack of awareness that has been drawn to the fashion industry as 63% of the remaining 68% answered with a lower figure. This was what fuelled me to write this essay and produce my artefact as I believe if awareness increases, consumption of clothes will decrease or become more sustainable.

Initial Ideas

I began with researching into the fashion industry as a whole and came across Stacey Dooley’s documentary “Fashion’s Dirty Secrets”. This then fuelled further research into denim and how ethical its production is. I started by searching basic facts which I found surprisingly shocking, such as how much water is used in the production of denim, and made me realise I needed to produce an investigative piece of writing which will stand out and be effective to whoever reads it. To gather a base for my essay I decided to investigate the history of the fashion industry as a whole and discover when the idea of fast fashion came about. During my initial research I found that the topic I had chosen, ethical fashion, had multiple different pathways which I could take. I found that I was occasionally going off on tangents which weren’t necessary for my project. This forced me to narrow down my title and make a new focus point of ethical consumption, how it relates to fast fashion and then using denim as my example. With fashion being an everyday commodity for many and consumption increasing dramatically in recent years due to high street shops moving online, I thought this focus point was very topical.

Title

My working title was ‘To what extent is the production of denim ethical?’ but found this didn’t cover the aspects that I wanted to include in my essay. For me the title was one of the hardest decisions of my EPQ as I wanted to include a range of ideas from different sections of the fashion industry, such as the Rana Plaza factory collapse, but couldn’t find a word or phrase which covered all of it. I resorted to mind mapping a variety of words which came to mind when someone said ‘Fashion’. This helped to visualize which words didn’t fit and which did. I came to the decision that I definitely wanted the phrase ‘Fast fashion’ in my title as this was the centre point of all my research and what caused the most detrimental environmental and social damage caused by the fashion industry. I then established the title ‘Is ethical and fast fashion mutually exclusive in the investigation of denim?’ but once I had completed most of my essay, I found this still didn’t quite fit with what I was writing about as I wasn’t including denim as much as I thought I was. Finally, I came to a decision and created my final title; ‘Are ethical purchases and fast fashion mutually exclusive? An investigation of denim.’ this allowed a subtle separation between my artefact and essay.

Product

My product is a denim jacket produced from unwanted and old denim items, such as jeans and skirts, with effective quotes and facts printed onto the back. I spent a concentrated week and a half producing the jacket as I find this is how I perform best, meaning I was less likely to miss a step. I then produced the printed writing separately to avoid mistakes and sewed these onto the jacket to make a more authentic finish. Furthermore, this allows me to change and adapt the writing as I can easily unpick it and replace it with an up-to-date figure.

Research

I used a vast array of different research sources throughout my project including; articles, documentaries and online courses. For my essay aspect of my project I used information from articles produced by newspapers, such as The Guardian, and organisations, such as Fashion Revolution, and online journals produced by various scholars. On the other hand, for my artefact I used predominantly Pinterest for inspiration alongside google images for which facts and figures to use on the back. During the production of my artefact I followed SimplicityVideo (2019) which was a guidance video on how to use the pattern piece, this was the most useful resource as if I got stuck when using the pattern piece, I could turn to this video for guidance.

Get Help With Your Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional essay writing service is here to help!

Furthermore, I discovered what people’s perceptions were on ethical fashion when I created and gave out a questionnaire to female participants aged between 14-27 years old. This allowed me to get an insight into the participants’ views and what their fashion consumer habits are like, at the end of this research I gained 266 results which allowed me to gather a reliable mean.

Target Audience

My main target audience is between 13-30year olds as this is typically when consumption is highest and one of the main ways to raise awareness is through social media as it’s such a significant platform where information gets shared around.

Skills I have learnt

As Art and Design is one of my A-Level subjects I already had an insight into textile production and the basics of how to use a sewing machine, although, I had not yet produced such a significant item of clothing meaning it came with challenges and skills I had to learn. As I was using a machine which I had not previously used before, I had to learn how to produce a button-hole. This was a challenge as I had to do it manually instead of using a button-hole presser foot which would normally construct the size of button-hole to fit the button you were using. In my case, when practising this new skill, it became difficult to produce the same sized button-holes, causing me to adapt and sew slightly slowly to produce the finish I wanted.

On the other hand, when designing my survey, I used the software programme Survey Monkey. This was a new experience and taught me how to design each question to fit the data I wanted to collect. It also taught me how to incorporate an image into a question to help educate the sample group and hence receiving their perception on the statement. This will definitely be a useful skill for future assignments at university.

Challenges and strengths

For my artefact the major challenge I faced, as previously mentioned, was producing the button-holes to be all the same size. To overcome this, I reduced the speed at which I was using the machine so I could line up each button-hole according to the markings which I had drawn out. This created a neat finishing to the front of the jacket and resulted in the buttons being in a straight line.

My time management didn’t go to plan as the write up of the essay took longer than expected and I wanted to do the production of the jacket within a concentrated time gap, this resulted in the production of the jacket being later than planned. However, when it came to the time gap, which I had left to complete the jacket, it allowed me to get a neat finishing as I knew which steps had been completed and which hadn’t.

Evaluation

If I were to do this project again, I would create a time gap to produce my jacket earlier in the year as then I would be able to keep up with the paperwork afterwards. This would enable time to go back and adapt the jacket if I changed my mind, but also enable me to develop the design.

Following on from this, if I were to resend my questionnaire out again, I would adapt and add slightly different questions, such as how much clothing they waste. This would have given me an insight into the waste a typical consumer is likely to produce, which is a significant contributor to the environmental impacts. I would have also changed the first question which was asking what type of education they were currently in, and I would just directly ask them for their age. This would have allowed me to investigate which age groups were more willing to change their ways and which weren’t.

When researching into this topic, I had to be careful of bias sources. This was due to my topic of fast fashion being very subjective. For example, the Stacey Dooley documentary was produced to make consumers realise the problems they are indirectly causing but also greatly encouraging the consumer to stop or significantly reduce their consumption of clothes. This may be seen as a bias article as it is over emphasising the impacts of fast fashion, causing me to question the reliability of this specific source.

Overall, I am pleased with how my artefact turned out as I feel it is effective, eye-catching and neat. I would not have changed my design of my jacket and I feel I have successfully incorporated all the ideas I wanted when I was completing my initial research.

Background of topic

Development of the fashion industry

Annie Radner Linden is an undergraduate social scientist student attending Bard College in New York. Her research into fast fashion has revealed that buying clothes ‘ready-made’ was closely aligned with Britain’s Industrial revolution, and the demand to buy these ready-made garments was powered by the “slop shop”. Linden states that the “slop shop” is a name for second-hand clothes shops which sold clothes of that time, growing in popularity in the 1600s and 1700s and is similar to a thrift shop in today’s world (Linden, 2016)

1600-1700

The “slop shop”

Englishman Thomas Saint designed the first sewing machine of its kind. The patent described a machine powered with a hand crank to be used for leather and canvas (Jonella, 2017).

Initial design of the sewing machine

1790

During the enclosure movement, factories began to be constructed and people started to migrate into the city for the new work opportunities. Some may say this was when the garment industry was really established and became the low-capital, labour intensive industry that it is known for. This boosted the textile industry significantly and quickly made the ‘ready-made’ garment a commodity people wanted more so than making the garments themselves. Although, originally ‘ready-made’ clothes were a specialised commodity aimed towards wealthier, higher classed consumers, it quickly became a mass-produced item which were sent off in batches to specific companies. (Linden,2016)

The Enclosure Movement

1801

The enclosure movement was the building block of our current fast fashion industry, developing into attaining the newest trends at a fraction of the original, designer price.

21st century

Present Day

Geographical Impacts

One of the most well-known examples of land degradation, as a result of intensive cotton farming, is the shrinking of the Aral Sea. The Aral Sea is located between Kazakhstan, in the North, and Uzbekistan, in the South and was formerly one of the largest inland seas in the world (Atanivazova, 2003). Now, more than 60% of water has disappeared in the last 30 years due to the water being mismanaged and diverted to be used to irrigate cotton fields.

This has resulted in more than 40,000km² of the heavily saline seabed being exposed, fuelling the rapid growth of wild plants (Atanivazova, 2003). As a consequence, the degradation and desertification of local ecosystems has and is still increasing. This is most notable in the marine life, causing 40,000-60,000 fishermen to lose their livelihoods, impacting the local economy greatly.

1989

2008

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aral_Sea_1989-2008.jpg

https://www.trekearth.com/gallery/Asia/Uzbekistan/West/Nukus/Moynaq/photo903696.htm

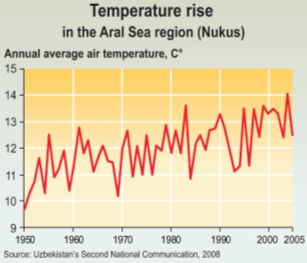

seen an increase in air temperature. However, estimates predict an increase in future temperatures ranging from 1.75 to 2.25°C on average in the region by 2050. Nevertheless, there are global factors which could influence and exaggerate this figure, such as the increased greenhouse emissions we are emitting into the atmosphere.

The fashion industry is a guilty player to this. According to a report by Alden Wicker (2017), “the fashion industry is responsible for the emission of 1,715 million tons of CO2 in 2015, about 5.4% of the 32.1 billion tons of global carbon emissions in 2015”. The date of when this figure was recorded decreases it’s reliability as it was collected 4 years ago, although if a follow up of this data would be released, we would, in an ideal world, see a decrease in this figure. However, we have seen an increase in these values coinciding with the growth of the fashion industry.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/zoienvironment/7548299436

Once these figures were published, the media was in uproar and activist groups were using their voices louder than ever, consequently causing a ‘lost in translation’ moment as the fashion industry was labelled the second most polluting industry in the world just below the oil industry (Sustain Your Style 2017). This term spread like a wild fire when it was used in the film “The True Cost,” released in 2015 by Andrew Morgan, which millions have streamed on multiple online streaming services (The True Cost, 2015).

This misconception, of the fashion industry being the second most polluting industry, came to light quickly after “The True Cost” was released, causing journalists on another spree of ‘who to blame’ as the figures originally released clearly indicate the fashion industry as tied 5th polluting, alongside the livestock industry (Wicker, 2017).

Wicker, 2017

Overall, the fashion industry as a whole is an ever-growing contributor to global warming and hence climate change within the Aral Sea region. Regardless of its ‘position’ on a table, with the industry using resources and contributing to each industry it sits below, for example cotton is an agricultural product and electricity powers the factories. Therefore, as the fashion industry continues to grow so will the industries which sit above it, creating a never-ending, consumer snowball effect which will inevitably lead to a climate emergency. In comparison, if fast fashion brands start to incorporate sustainable management schemes into their production lines, then it would benefit other industries and in the long term reduce the rate of climate change.

As awareness and attention is increasingly being drawn to the growing threat of plastic in our oceans in relation to climate change, activists are coming up with solutions to combat this, such as in the reduction of plastic straws. However, a major contributor to this global phenomenon is that of Polyester. As Polyester is the most popular fabric used in the fashion industry it is always in demand. Although, when polyester garments are washed in domestic washing machines, they shed microfibres that add to the increasing levels of plastic in our oceans. These microfibres are minute and can easily pass through sewage and wastewater treatment plants into our waterways, but as they do not biodegrade, they represent a serious threat to aquatic life. Small creatures such as plankton eat the microfibres, which then make their way up the food chain to fish and shellfish eaten by humans (Messinger, 2016).

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/polyester-care-label.html

Moreover, Polyester and other synthetic fabrics require large amounts of crude oil in their manufacturing, releasing emissions including volatile organic compounds, particulate matter, and acid gases such as hydrogen chloride. All of these can cause or exacerbate respiratory diseases, according to Luz Claudio, a tenured professor of environmental medicine and public health at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. (Claudio, 2007).

Social Impacts

However, it is not only environments and animals which are being destroyed and affected by this ever-growing industry. In 2013, at the Rana Plaza complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh, more than 1100 people were killed when a clothing factory collapsed, making it the world’s worst industrial accident since the Bhopal disaster in India in 1984 (Hobson, 2013). This factory collapse was caused by structural weakness due to the building being built too tall. Although this could have been mitigated as the factory owners had been repeatedly asked to close down the factory due to the appearance of severe cracks. Furthermore, the building did not meet local construction standards as it had been built three storeys too high to what it was originally designed to be. This is not just an anomaly as it had been discovered that over 90% of Dhaka’s high-rise buildings do not meet the local construction standards (Hobson, 2013).

MUNIR UZ ZAMAN/AFP/Getty Images

https://www.itv.com/news/2013-10-24/primark-time-rivals-also-pay-bangladesh-factory-victims/

As distressing as this incident was, the fashion industry rocketed on, keeping up with the pace of new fast fashion trends. So much so that the factory which collapsed supplied high street shops such as Primark and Matalan, but more shockingly the clothes produced the same day of this incident were on the shelves within a week.

Within these factories, there are greater underlying social impacts amongst the workers. This includes problems such as workers’ rights, poor working conditions, long hours, low wages, child labour and health and safety issues, these are especially still major concerns in developing nations such as Bangladesh (Kozlowski, Bardecki and Searcy 2012).

But who are these invisible workers? Who are the victims of our consumptions? The ones we hear about who work day in day out to supply us with clothes just so they can get a meal for their family. According to Remake, a non-profit organisation, 75 million people work in the garment industry, and of this 80% are women between the ages of 18-34 (Veridiano 2018). These women, who may be sewing shirts for major fast fashion brands in a Bangladeshi factory, only earn a total of 33 U.S. cents an hour, working an average of 60 hours a week and even then, struggling hugely to pay their bills (Peters 2018).

In comparison to many jobs in developed countries, work days are not set on a strict schedule. These workers could be working from 8am to 9pm one day and the next they could be forced to work till 3:00am. So how are shops changing their ways?

http://www.takepart.com/article/2016/10/25/will-hearing-from-garment-workers-change-fast-fashion/

As a whole, multiple high-street brands have released various statements over the years, putting the consumer’s minds at rest that they are sourcing sustainably and that ethical working conditions are in operation. However, the high street shops rarely own the factory they are importing from, meaning the owner can change working hours, working conditions and wages whenever they wish. Primark, one of the UK’s biggest and well-known contributor to fast fashion, claims that they hand pick the factories in which they produce their clothes and “each factory is vetted to internationally-recognised standards set out in the Primark Code of Conduct.

This Code covers areas such as pay, employment policies and health and safety.” (Primark, 2019). Within this, their Ethical Trade and Environmental Sustainability Team checks on each factory to make sure they are running appropriately but also to try and improve their overall business. Although, a major feature falls through this frame work which is the insurance of a living wage, which is difficult for Primark to regulate and control due to the infrequency of their visits to the factories. Surprisingly, Primark scores a considerably lower score on the Fashion Transparency Index then its high street competitors, scoring only 35% in comparison to H&M which scored 61%. As of 2019, the highest scoring brand is Adidas with a score of 64% and lowest being Tom Ford. However, Adidas has not dealt with the problems at hand as this is the third year (index has only been in place for 3 years) running it has topped the charts with a rapidly increasing score. (Ditty, 2019).

https://www.fashionrevolution.org/faqs-fashion-transparency-index-2017/

Communities located around factory areas also suffer significantly as a result of the toxic waste which is dumped in local waterways or in local fields. A major hub for jean production is in Xintang, China where 1/3 of our jeans we buy come from. Greenpeace analysed 21 samples of water from various waterways in Xintang and found that 17 of these contained highly toxic heavy metals all coming from the chemicals used to dye and finish our jeans, such as mercury, cadmium, lead and copper (Fashion Revolution, 2017). These chemicals are so polluting that waters in the area turned blue from the indigo dye used in our jeans, but it isn’t just in the water systems. Blue particles of dust gather in streets causing workers’ and locals’ lungs to become embedded with fine silica, leading to silicosis which is a serious lungs disease.

Find Out How UKEssays.com Can Help You!

Our academic experts are ready and waiting to assist with any writing project you may have. From simple essay plans, through to full dissertations, you can guarantee we have a service perfectly matched to your needs.

View our academic writing services

Xintang, the denim’s world capital, is home to the production of approximately 260-300 million pairs of jeans per year and retail between US$5.99 to anything up to US$99.99, shadowing the significant social and environmental costs. Along with the toxic waste which is distributed into local waterways and fields, a single pair of jeans uses approximately 9,500 litres of water in its production, exasperating drought in these vulnerable areas.

http://www.greenpeace.org/eastasia/news/stories/toxics/2010/textile-pollution-xintang-gurao/

What can you do?

As a regular consumer it is too easy to think ‘I’m just one consumer, what difference am I going to be making’ but if each person were to say or think that, then how would anything change or develop in today’s world. So, what can you, as a consumer, do? Well as the sustainable fashion brand Reformation states “being naked is the number 1 most sustainable option”, as much as this may be true, there are other options, such as:

- Purchasing from sustainable fashion brands.

- Repairing or restyling damaged clothes.

- Reselling or donating your unwanted clothes.

- Reducing your consumption as a whole.

- Purchasing higher quality clothes that last longer meaning you buy less.

- 5 ways to check a garment is well made (Sustain your Style, 2017):

- Check the stitching – when you pull the seams does it hold well.

- Thickness of fabric – hold it up to the light to assess the thickness of the fabric, generally the thicker the fabric, the higher the quality.

- Zipper – metal zippers are way better then plastic.

- Buttons – have the buttons been sewed on securely, do they look like they are hanging by a thread?

- Patterned fabric – does the pattern on the fabric match up at each seam?

Purchasing from sustainable fashion brands, such as Reformation, can financially be a significant step up. However, there are ways to avoid this, such as shopping at charity shops, these can be more affordable and benefit other people. Also shopping from online resale companies such as Ebay or Depop can offer you a wider variety of options. Moreover, there has been an increasing demand for vintage clothing especially from the younger generation, this has resulted in vintage high street stores opening up in major cities, these can offer branded commodities but at a fraction of the retail price.

Conclusion

To conclude, most ethical purchases cannot be found within fast fashion as most ethical clothing brands do produce sustainable items of clothing quickly and keep up with upcoming trends, however, they are not cheap purchases. In my opinion this is due to the lack of demand resulting from very little awareness to the subject, as other high street brands have started to produce clothes from organic resources but still put them on the market at cheaper prices. Such brands include ASOS and H&M, who have multiple items of clothing produced from recycled polyester to organic cotton. Although, in my point of view these are not considered ethical purchases, but more sustainable alternatives, as they are still made within poorly controlled factories where workers gain little income and work in poor conditions. This is an increasingly common marketing technique used by high street brands to cover up previous faults and lure in more customers. However, they still don’t give all the information which should be given for it to be an ethical purchase, such as where and which factory the items of clothing were produced. On top of this, when scrolling through the sustainable section of H&M’s website I came across a nice jumper made from recycled polyester, however, when I clicked on it and looked at the composition of it, only 60% was recycled polyester. On the other hand, it is still a start to making products more sustainable and improving the consumer’s mind set.

After researching into this topic, the main way to improve people’s perception of ethical consumption is to teach and raise awareness of the subject. I found this extremely evident when analysing my data from a questionnaire I had sent out for females aged between 14-27 years old. I gave them the statement “It takes about 2700 litres of water to make one shirt, which is how much we would normally drink over a 3year period” (WWF,2013) and found that after reading this statement 184 (which was 69.17%) of the participants would consider reducing their consumption of clothes and 89.86% would pay more if the item of clothing was ethically produced.

I do feel major fast fashion companies are changing their ways but it will be in the distant future when ethical purchases are the new fast fashion and fast fashion will no longer cause detrimental damage to the environment, workers and locals living in vulnerable areas. I also hope that with the help of new sustainably managed technology and expertise, more factories will mass produce recycled materials and improve the working conditions of the workers. Nevertheless, with social media expanding and people being able to buy commodities at just a click of a button, the fashion industry has a significant battle to face if they don’t change their clothes now.

-

Ataniyazova, O.A (2003) Health and Ecological Consequences of the Aral Sea Crisis, prepared for the 3rd World Water Forum Regional Cooperation in Shared Water Resources in Central Asia Kyoto, March 18, 2003. Available at (http://www.caee.utexas.edu/prof/mckinney/ce385d/papers/atanizaova_wwf3.pdf) First accessed on 30/5/2019 .

Bibliography

- Claudio, L (2007) Waste Couture: Environmental Impact of the Clothing Industry, Environmental Health Perspectives, 115(9): 449-454

- Ditty, S (2019) Fashion Transparency Index. 2019 edition. Publication location unknown: Fashion Revolution.

- Express., (2019) New clothes bought in UK produce more CO2 than journey round the world – six times! [online] Express [viewed 30/08/19] available from https://www.express.co.uk/life-style/style/1171517/New-clothes-UK-CO2-journey-round-world

- Fashion Revolution., (2017) What My Jeans Say About the Garment Industry [online] Fashion Revolution [viewed 04/06/2019]. Available from https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/What-My-Jeans-Say-About-the-Garment-Industry.pdf

- Hobson, J (2013) To die for? The health and safety of fast fashion, Occupational Medicine, 63(5): 317–319.

- Jonella (2017) History of the Sewing Machine: A Story Stitched In Scanda, Contrado, available from (https://www.contrado.co.uk/blog/history-of-the-sewing-machine/) accessed on 23/07/19.

- Kozlowski, A; Bardecki, M and Searcy, C (2012) Environmental Impacts in the Fashion Industry: a lifecycle and stakeholder framework, JCC, 45:15-34

- Linden, Annie Radner, (2016) “An Analysis of the Fast Fashion Industry”. Senior Projects Fall. 30: page 4-6

- Messinger, L. (2016) How your clothes are poisoning our oceans and food supply. The Guardian [online] 20 June. [viewed 30/05/2019] Available from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jun/20/microfibers-plastic-pollution-oceans-patagonia-synthetic-clothes-microbeads

- Peters, A (2018) Why this clothing company is making its factory wages public, Fast Company, 08.08.18, available from: https://www.fastcompany.com/90213069/why-this-clothing-company-is-making-its-factory-wages-public accessed on: 13/04/2019

- Primark (2019) People and production. Available from https://www.primark.com/en/our-ethics/people-and-production/a/0c2214ed-454f-4344-9b07-00f20678edab accessed on: 11/07/2019

- Simplicity video (2019) Sew This Jeans Jacket by Mimi G for Simplicity Patterns [online] YouTube [viewed 03/08/2019] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bdC9_JVPmmQ

- Sustain Your Style (2017) Fashion’s Environmental Impact, SustainYourStyle, available at https://www.sustainyourstyle.org/old-environmental-impacts accessed on: 25/08/2019

- Sustain Your Style (2017) How can we reduce our Fashion Environmental Impact? [online] Sustain Your Style [viewed 25/08/2019] available from https://www.sustainyourstyle.org/en/reducing-our-impact

- The True Cost (2015). [Online] Directed by Andrew Morgan. Cannes: Untold Creative [viewed on 05/01/2019]. Available from: Amazon Prime Video

- Thompson (2008) The Aral Sea Crisis. Available from http://www.columbia.edu/~tmt2120/environmental%20impacts.htm Accessed on 30/5/2019.

- Veridiano, R (2018) Why Sustainable Fashion Is Important For Asian-American Women, Remake, available from: https://remake.world/films/why-sustainable-fashion-is-important-for-asian-american-women/ accessed on: 13/05/2019

- Wicker, A (2017) PLEASE stop saying fashion is the 2nd most polluting industry after oil. EcoCult, May 9, 2017, Available at https://ecocult.com/now-know-fashion-5th-polluting-industry-equal-livestock/ accessed on 10/07/2019.

- WRAP (2019) Clothing [online] WRAP UK [viewed 03/08/2019] available from http://www.wrap.org.uk/content/clothing-waste-prevention

- WWF Stories (2013) The Impact of a Cotton T-Shirt – How smart choices can make a difference in our water and energy footprint [online] World Wildlife [viewed 20/05/2019] available from https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/the-impact-of-a-cotton-t-shirt

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: