Jean Piaget (1896–1980) was a Swiss psychologist whose pioneering work on child cognition laid the foundation for developmental psychology. With Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development, he introduced the idea that children are not “mini adults” in their thinking; instead, they progress through qualitatively different stages of understanding. Piaget’s background in natural sciences and philosophy shaped his approach – he described himself as a “genetic epistemologist,” studying the origins of knowledge.

Get Help With Your Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional essay writing service is here to help!

His observations of children (including his own) led him to conclude that knowledge is actively constructed by the child through interaction with the world, rather than passively absorbed or innately pre-formed. This constructivist viewpoint revolutionised how we view learning and cognitive development in childhood. Piaget’s stage theory of cognitive development remains one of the most influential frameworks in psychology, providing insight into how thinking and reasoning evolve from infancy to adolescence. Understanding Piaget’s theory is essential for students of psychology and education, as it offers a systematic map of cognitive growth and has informed teaching practices and further research for decades.

The Four Stages of Cognitive Development

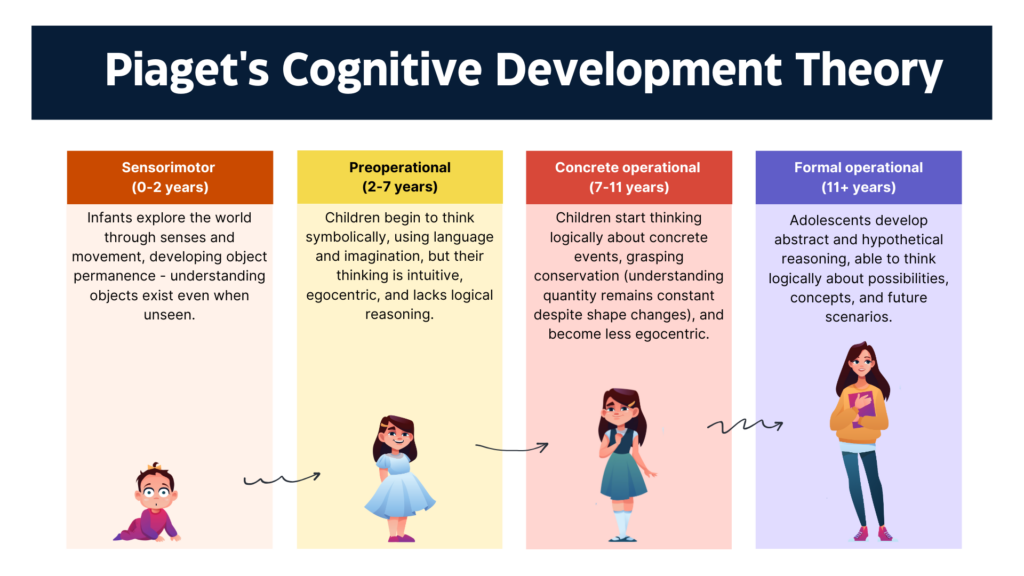

Piaget proposed that cognitive development unfolds in a series of four universal, sequential stages from birth through adolescence. Each stage reflects a distinct way of thinking and understanding the world. The stages always occur in the same order; you cannot skip a stage, and each stage builds on the accomplishments of the previous one. Below, we explain each stage with its key characteristics and examples:

Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to ~2 years)

In the sensorimotor stage, infants learn about the world through their senses and actions. At birth, a baby’s cognition consists of just simple reflexes (e.g. sucking, grasping). But over the first two years these actions become more intentional and coordinated. Babies “think” with their eyes, hands, ears, and other sensorimotor equipment before they have language. A hallmark achievement of this stage is the development of object permanence – the understanding that objects continue to exist even when out of sight.

For example, Piaget observed that a 6-month-old infant would not search for a toy hidden under a blanket, as if it ceased to exist; by contrast, an 18-month-old would actively look for it, indicating they remember and believe the toy still exists. In gaining object permanence, the infant moves from merely experiencing “here and now” sensations to forming mental representations of objects and events. By the end of the sensorimotor period (around 2 years), toddlers can engage in simple pretend play and deferred imitation (imitating actions seen earlier), showing they have some internal representations of the world. Overall, characteristics of this stage include rapid growth in sensorimotor skills and the transition from reflexive behaviour to goal-directed activity.

Preoperational Stage (2 to 7 years)

The preoperational stage is the period when children begin to represent the world internally through language, imagery, and symbolism. Piaget noted that around age 2, children enter a phase of “semiotic function” – they can form mental representations of objects and events that aren’t currently present. This newfound representational ability is evident in symbolic play (make-believe games), drawing, and the explosive development of language.

For example, a child might use a banana as a pretend telephone, demonstrating the use of one object to stand for another in play. Children in this stage can think in images and symbols, but their thinking is not yet logical or organized. They tend to be egocentric, meaning they struggle to see perspectives other than their own. Piaget’s classic Three Mountains experiment illustrates this: a preoperational child looking at a model landscape will assume that another observer (e.g. a doll) sees exactly the same view that the child sees because the child cannot easily imagine the other perspective.

Another hallmark of this stage is a difficulty with conservation tasks – understanding that certain properties of objects (like volume, number, or mass) remain the same even when their appearance changes. For instance, if you pour water from a short wide glass into a tall thin glass, preoperational children often insist the tall glass has “more” water, focusing on height while ignoring width. This limitation is due to centration (focusing on one aspect of a situation) and an inability to mentally reverse operations.

In summary, during the preoperational stage, children excel at pretend play and language, yet their thought is intuitive and egocentric, lacking the structured logic of later stages.

Concrete Operational Stage (7 to 11 years)

In the concrete operational stage, roughly ages 7 to 11, children’s thinking becomes more logical and organized. However, this occurs mainly in reference to concrete objects and events. Piaget observed that the egocentrism of earlier years diminishes – school-age children become better at taking others’ viewpoints and are less fooled by appearances. A key development in this stage is mastering the concept of conservation. Children come to understand that quantities remain constant despite changes in shape or arrangement. For example, a concrete-operational child:

- will recognize that water poured into a differently shaped glass is still the same amount, or;

- that a lump of clay reshaped into a ball or a sausage has the same mass.

They also grasp concepts of reversibility (that actions or changes can be undone in their mind) and classification. Children can organise objects into hierarchies of classes and subclasses – for instance, knowing that roses and daisies are both types of flowers, and hence a rose is both a rose and a flower (demonstrating an appreciation of class inclusion). They can also arrange items along a quantitative dimension (like ordering sticks by length), showing seriation ability. However, their logical reasoning ties mostly to tangible, concrete information they can directly manipulate or observe. Abstract or hypothetical situations (e.g. “what if” scenarios that involve variables not present in the immediate environment) are still challenging. In this stage, thinking is logical but concrete: children can solve problems based on real objects or direct experiences but have difficulty with purely abstract reasoning.

Formal Operational Stage (11 years and up)

The formal operational stage emerges around 11 or 12 years and continues through adolescence into adulthood.. In this final stage, individuals develop the capacity for abstract, scientific, and reflective thinking. Adolescents can reason about hypothetical situations, consider possibilities that contradict reality, and systematically test ideas. Piaget found that at this stage, youth can perform hypothetico-deductive reasoning – starting with a general hypothesis or principle and deducing specific outcomes, as in scientific problem-solving. They can also engage in propositional thought, evaluating the logic of statements without needing concrete examples (for example, understanding that if A < B and B < C, then A < C, even with A, B, C as unknowns).

A classic experiment is the pendulum problem: when asked what factors influence a pendulum’s swing, formal operational thinkers will systematically vary the length of the string, weight, and force of push to isolate variables and discover the correct principle. By contrast, younger concrete thinkers may change variables haphazardly or focus only on what’s they directly observe (e.g. thinking only the push matters). Formal operational individuals can imagine multiple outcomes to problems, think about moral, philosophical, and social issues in depth, and plan for the future more effectively.

However, Piaget noted that attaining formal operations is not an overnight change at 11 – it develops throughout adolescence. Also, subsequent research has found that not all adults use formal thinking in every domain (people may be formal thinkers about topics they have experience with, but use more concrete reasoning in unfamiliar areas). Nonetheless, the formal operational stage represents the pinnacle of logical thinking in Piaget’s model, where reasoning is flexible and abstract.

Key Concepts in Piaget’s Theory

Piaget’s theory introduced several fundamental concepts to explain how children progress through the stages. These include schemas, the mental structures that underlie thinking, and the processes of assimilation and accommodation that drive cognitive growth, as well as specific notions like object permanence and conservation.

Schema (plural: Schemas or Schemata)

Piaget defined a schema as a mental framework or organised pattern of thought that children (and adults) use to interpret and respond to situations. In other words, a schema is like a concept or category in the mind into which we fit our experiences. Early in life, babies have very simple schemas tied to actions (for example, a sucking schema or a grasping schema). As children interact with their physical and social environment, their schemas become more complex and abstract.

For instance, an infant’s “dog” schema might be based on the family pet; as the child grows, this schema expands to include different breeds of dogs and perhaps subdivides into related schemas (dogs vs. cats, etc.). Schemas are the building blocks of knowledge, and Piaget believed cognitive development is essentially the continuous refinement and transformation of schemas.

Assimilation and Accommodation

Piaget proposed that learning occurs through an ongoing process of adaptation to new information. Adaptation has two complementary aspects: assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation is the process of incorporating new experiences into existing schemas – essentially, it’s about fitting new information into what one already knows.

For example, if a young child knows the schema “bird” (things with wings that fly), upon seeing a butterfly, the child might call it a “bird,” assimilating the butterfly into her existing schema of flying creatures. Accommodation, on the other hand, is when they modify existing schemas (or create new ones) to adjust to new information that doesn’t fit. If the child learns that butterflies are not birds, she may adjust her schemas – perhaps narrowing “bird” to exclude insects and creating a new category for “butterfly.” In this way, her mental frameworks change to reflect the new reality. Piaget viewed assimilation and accommodation as the twin engines of cognitive development, working in tandem.

When children encounter something new, they first try to assimilate it into what they already understand; if it doesn’t quite fit, it creates an imbalance (or cognitive dissonance) that drives accommodation, changing their thinking to restore equilibrium. Through countless cycles of assimilation and accommodation, a child’s schemas become increasingly adapted to the world. Piaget called this balancing act equilibration – the self-regulation process that keeps cognitive structures in tune with the environment.

Object Permanence

Object permanence is a specific concept. Namely, the understanding that objects continue to exist even if you cannot seen or hear them. Piaget discovered object permanence through his observations in the sensorimotor stage. Early in the first year, infants act as if a hidden object has ceased to exist; by about 8–12 months, they start to search for objects that disappear from view, indicating a developing notion that the object still exists somewhere. Piaget famously demonstrated object permanence with a simple experiment: he would hide a toy under a cloth while the infant watched. Babies younger than about 6 months tended not to search for the hidden toy, as if unaware it still existed; by around 18–24 months, most infants would actively look for the toy under the cloth.

This suggests that by the end of the sensorimotor stage, children have a robust concept of object permanence – they know that people and things have a continuous existence independent of the child’s immediate perception. Experts conclude that object permanence is a fundamental milestone because it signifies the emergence of mental representation.

Interestingly, later research using different methods (such as measuring infants’ gaze and surprise rather than requiring them to reach for hidden objects) found that some understanding of object permanence may exist even earlier than Piaget believed – as early as 3 to 5 months of age. Nonetheless, Piaget’s work on object permanence was groundbreaking, revealing that infants’ worlds are qualitatively different from adults’ and that a sense of a permanent world is gradually constructed in infancy.

Conservation

In Piaget’s context, conservation refers to the understanding that certain properties of objects (such as quantity, volume, number, or mass) remain the same even when their outward appearance changes. Piaget identified that children in the preoperational stage typically fail to conserve, whereas those in the concrete operational stage succeed. Classic Piagetian conservation tasks involve showing a child two equal quantities, transforming one in appearance, and then asking if they are still equal.

For example, one task shows two identical short glasses with the same amount of liquid; then, the liquid from one glass is poured into a tall, thin glass. A preoperational child often says the tall glass has more liquid (focusing on height), whereas a concrete operational child will say the amount is still the same, recognising that height increase is compensated by narrower width. Other conservation tasks Piaget used included: rolling one of two equal clay balls into a sausage shape (does one have more clay now or are they equal?); spreading out one of two equal rows of coins (does the longer row have more coins?); etc. Success on conservation tasks demonstrates the child’s ability to decenter (consider multiple aspects of a situation) and to perform mental reversals (imagine pouring the liquid back or rolling the clay back to the original shape).

Piaget found that most children acquire conservation of number, length, and liquid by around 6–8 years, and conservation of mass and weight a bit later (up to 9–10 years). Conservation is a key indicator of logical thinking in the concrete operational period and shows that a child has overcome the intuitive, appearance-bound reasoning of earlier ages.

Piaget’s Experiments and Observations

Piaget’s theory was not just abstract speculation. Rather, he grounds it in ingenious experiments and careful observations of children. He used what he termed the clinical method: a flexible question-and-answer technique to probe children’s thinking, often combined with simple tasks or puzzles. Here are a few of Piaget’s well-known experiments that led to his insights.

Object Hiding Task (Object Permanence)

As described earlier, Piaget would hide an attractive toy under a cloth or behind a screen to see if an infant would search for it. He observed a qualitative change around 8–12 months when infants began to reliably search for hidden objects. In a related finding, Piaget noted a peculiar error made by infants between about 8–12 months, called the A-not-B error. Say, for instance:

- You hide a toy repeatedly at location “A” (e.g. under one cloth) and the infant retrieves it each time.

- Then, you hide the toy at a new location “B” in front of the child.

- Infants of that age often still looked for the toy at location A.

Piaget’s interpretation: the A-not-B error is evidence that the infant’s object concept was still tied to their own actions (the memory of finding it at A) rather than a fully independent idea of the object.

These simple hiding games provide evidence for the gradual emergence of object permanence in the sensorimotor stage.

Three Mountains Task (Egocentrism)

To assess young children’s ability to take another’s perspective, Piaget devised the three mountains experiment.

- He showed children a model of three mountains of different sizes and colors, with distinctive features on each side.

- He would place the doll sitting at a different point around the mountains.

- Finally, he asks the child to choose, from a set of pictures, what the doll would see.

Preoperational children (around 4–5 years) often pick the picture representing what they themselves saw, demonstrating egocentrism. That is, they assume the doll’s perspective was the same as their own. Only later, as children approached the concrete operational stage (6–7 years and up), did they choose the correct picture corresponding to the doll’s viewpoint, indicating they could decenter and imagine another perspective.

The Three Mountains Task today serves as a vivid demonstration of the young child’s egocentric thought in Piaget’s theory.

Conservation Tasks (Logical Thinking)

Piaget conducted numerous experiments to test whether children understand conservation of various quantities. For example, in the conservation of liquid task, he would pour water between containers of different shapes as described above, then ask the child if the amount of water was still the same or which had more. In the conservation of number task, he would show two identical rows of coins or counters equally spaced; then he would spread out one row, making it longer. Preoperational children typically say that the longer row had more items, while concrete operational children correctly say the number does not change.

Piaget also tested conservation of mass (reshaping clay) and conservation of length (offsetting two equal sticks), among others. These experiments revealed the developmental shift from intuitive reasoning to logical reasoning that defines the concrete operational stage. Piaget’s findings show that until around age 6 or 7, the immediate perceptual appearance of things will sway children. Whereas older children begin to understand underlying invariants.

Combination of Chemicals (Formal Reasoning)

With adolescents, Piaget and collaborator Bärbel Inhelder presented problems that required systematic, scientific reasoning – for instance, the combination-of-chemicals problem. Teens were given several colorless liquids and asked to figure out which combination would produce a yellow color (this was a classic task in The Growth of Logical Thinking, Inhelder & Piaget, 1958). Success required systematically testing hypotheses by combining the liquids in different ways.

Piaget found that younger kids approached it unsystematically or by random trial and error, whereas adolescents in the formal operational stage could methodically test combinations and use logical deduction (e.g. if Liquid A doesn’t turn yellow by itself or with B, try A with C, etc., and keep track of results) to solve the problem.

Another famous formal reasoning task is the pendulum problem. With the Pendulum Problem, formal thinkers discern that the length of the string (and not the weight or the strength of the push) is the key factor determining the pendulum’s period. These tasks supported Piaget’s idea that formal operational thinkers approach problems in a hypothesis-testing manner, akin to scientists, which is a leap from the concrete trial-and-error strategies of younger children.

Clinical Interviews

Aside from structured tasks, Piaget often engaged children in open-ended questions to probe their understanding of concepts like time, morality, and logic. For example, he would ask children where dreams come from, or whether a lying person who said something untrue by mistake is a liar. The rich qualitative data from these interviews illustrated how children’s reasoning changes with age.

Piaget’s conversational method allowed him to uncover not just what children know, but how they think about it – revealing, for instance, that a 5-year-old might think dreams are put into their heads by someone, whereas an older child understands dreams are generated by the mind.

The Design of Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Piaget’s experiments were often simple but cleverly designed to illuminate the structure of thought. While his methods lacked today’s standardised procedures or large samples, they provided profound insights. His findings – like the stages of object permanence and the systematic errors children make at certain ages – today are subject to replication. Moreover, they remain classic demonstrations in developmental psychology. They illustrate the progression from sensorimotor intelligence to abstract reasoning that Piaget mapped in his stage theory.

Comparison with Competing Theories: Piaget vs Vygotsky

Many contrast Piaget’s theory with that of Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934), another influential developmental psychologist. While Piaget emphasized the individual child’s active discovery and biological maturation, Vygotsky emphasized social interaction and culture as drivers of cognitive development. Here are some key differences between their approaches:

Role of Social Environment

Piaget believed cognitive development is largely a solitary process of the child exploring and interacting with objects, constructing knowledge through their own activity. Piaget recognises social input (from parents or peers), but it is not central to his theory. Rather, he saw development as unfolding according to a universal biological timetable, with learning following.

In contrast, Vygotsky argued that social interaction is fundamental. According to Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, children learn through guided participation and dialogue with more knowledgeable others (parents, teachers, peers). Cognitive skills are internalised from the social context. For example, where Piaget might see a child figuring out a puzzle on their own, Vygotsky would highlight how an adult’s guidance (hints, questions) could elevate the child’s problem-solving ability.

Stages vs. Continuous Development

Piaget’s framework is stage-based – he proposed distinct stages (sensorimotor, preoperational, etc.) that all children go through in the same sequence, with qualitative changes at each transition. Vygotsky did not outline stages of development.

Instead, he viewed development as a continuous process, heavily dependent on cultural context and language. Abilities emerge from social interactions and can be developed continuously with support. Thus, where Piaget saw development happening “inside-out” (internal maturation enabling new learning), Vygotsky saw it “outside-in” (social learning enabling new internal capabilities).

Learning and “Readiness”

Piaget introduced the idea of readiness – certain concepts (like conservation or abstract logic) cannot be fully understood until the child’s cognitive stage has matured. He cautioned against trying to teach children skills for which they aren’t developmentally ready, a stance sometimes referred to as “the American question” (whether cognitive development can be accelerated).

Vygotsky, however, believed effective teaching can lead development. His concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) describes tasks a child cannot do alone but can accomplish with help. Instruction aimed within the ZPD – slightly above the child’s current level – can hasten development. In practice, Piagetian educators might wait for signs of readiness before introducing certain lessons, whereas a Vygotskian approach would actively scaffold the child to reach the next level.

Language and Thought

Piaget saw language as a result of cognitive development – for instance, as children’s thinking becomes symbolic in the preoperational stage, their language explodes. He noted young children’s “egocentric speech” (talking to themselves) and believed it fades as they become less egocentric.

Vygotsky, by contrast, saw language as crucial in shaping thought. He interpreted private speech (children talking to themselves) as a tool of thought – children externalise their thinking to guide themselves through tasks, and this eventually becomes internalised as inner speech. In short, Piaget viewed thought -> language, while Vygotsky viewed social language -> thought.

Educational Implications

Piaget’s approach to education emphasises discovery learning and allowing children to explore and experiment on their own (hands-on learning). The teacher’s role is to provide appropriate materials and opportunities, then let learners construct understanding. Vygotsky’s approach places more emphasis on guided learning – teachers scaffold students’ learning by engaging them in dialogue, asking leading questions, and providing feedback. Cooperative learning (students working together) is also a Vygotskian strategy, leveraging social interaction. Piaget advocated letting children learn by doing with minimal adult intervention (“little scientists”), while Vygotsky encouraged leveraging guided participation and teaching through interaction.

It’s worth noting that despite these differences, both Piaget and Vygotsky saw children as active participants in their own development, and modern educational approaches often integrate both perspectives. For example, a teacher might set up a discovery activity (Piagetian) but also ask probing questions or hint at solutions (Vygotskian scaffolding) to stretch the child’s skills. In sum, Piaget’s theory is more focused on the individual construction of knowledge through stages. Whereas Vygotsky’s theory highlights the collaborative construction of knowledge through social and cultural means. Both theories have greatly contributed to our understanding of how children learn, offering complementary insights.

Find Out How UKEssays.com Can Help You!

Our academic experts are ready and waiting to assist with any writing project you may have. From simple essay plans, through to full dissertations, you can guarantee we have a service perfectly matched to your needs.

View our academic writing services

Piaget’s Theory of Play

Play is a vital activity of childhood, and Piaget studied it closely, particularly in his book “Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood” (1962). Piaget’s theory of play ties into his broader ideas of assimilation and accommodation. He viewed play as primarily an exercise of assimilation, where children incorporate experiences into their existing schemas for enjoyment rather than to obtain new information. In other words, in play, children are “masters of the situation” – they bend reality to fit their ideas rather than adjusting their ideas to reality. This makes play a pleasurable activity, as it is not constrained by the demands of accuracy or efficiency.

Piaget identified three main types of play, corresponding roughly to his first three developmental stages uva.theopenscholar.com:

Sensorimotor Play (Practice Play)

Predominant in infancy, this involves infants engaging in repeated actions and movements with objects or their own body simply for the pleasure of the movement. For example, a baby might repeatedly shake a rattle, babble sounds, or drop objects from a high chair over and over. According to Piaget, these repetitive actions are the infant’s way of exercising and consolidating their sensorimotor schemas. A baby throwing their head back to see the world from a new angle (as one of Piaget’s observations of his infant son) or an infant swatting at a mobile are examples of sensorimotor play. The child is not trying to learn something new; they are assimilating the world to their current schemas (e.g. “what I do causes things to happen”) and enjoying the results.

Symbolic (Pretend) Play

As children enter the preoperational stage, around age 2 onward, they begin to engage in make-believe and pretend play. Here, one object or action is used to represent something else – a stick becomes a sword, a doll “speaks,” or a child takes on roles like playing “mummy and baby.” Piaget saw pretend play as a hallmark of the developing ability to use symbols and mental representations. In pretend play, children assimilate reality to their wishes: if reality is not satisfying or is too complex, they simply modify it in their play scenario.

For instance, a child upset by a doctor’s visit might later play “doctor” with toys, re-enacting and thus assimilating the experience on their own terms. Piaget noted that pretend play often reflects children’s internal wishes or tensions (he even said children may replay unpleasant experiences in play as a way of assimilating and thereby processing them).

However, Piaget did not believe that pretend play in itself taught new skills or social norms – in his view, its function was more about consolidating existing knowledge and gratifying the child’s desires (he termed the function “ego-centric” because the child bends reality to self). Vygotsky, in contrast, argued that pretend play is crucial for development (for example, helping children learn self-regulation and abstract thinking), but Piaget was more sceptical of play‘s role in fostering new cognitive abilities.

Still, Piaget acknowledged that pretend play is a natural expression of the child’s emerging representational capacities in early childhood.

Games with Rules

In middle childhood (concrete operational stage), children become interested in rule-based games – from simple board games and card games to sports. Piaget noted that around 7+ years, play takes on a social, rule-governed form (e.g. playing marbles with agreed rules, or tag with fixed rules). These games with rules represent a transition: they involve accommodation to a shared reality.

To play a game, a child must understand and follow rules that are the same for everyone. That requires relinquishing a purely egocentric viewpoint and accommodating one’s behavior to the structure of the game. Piaget considered this the highest form of play, as it requires cooperation and the beginnings of moral understanding (following agreed-upon rules fairly). Unlike free pretend play, games with rules constrain assimilation – you can’t just decide a pawn moves any way you wish in chess, for example.

Therefore, they help children develop logic, strategy, and an appreciation for conventional rules. Piaget saw this as reflecting the child’s entrance into concrete operational thinking, where they can handle the structure of rules and understand that everyone must abide by the same set of agreed principles.

Theory of Play Summary

In summary, Piaget’s theory of play suggests that:

- play evolves from pure practice of sensorimotor schemes, to;

- imaginative rehearsal of symbolic ideas, to;

- structured games reflecting concrete operations.

Throughout, play is dominated by assimilation – it’s about doing what one knows for fun. Learning can certainly happen in play, but Piaget’s emphasis was that play by itself doesn’t seek to produce new knowledge; rather, it consolidates and exercises what the child has already learned. This perspective is sometimes contrasted with educational views that see play as a powerful learning tool. Today, many psychologists agree that play can contribute to learning (for example, pretending can expand language and social skills), aligning more with Vygotsky’s views. Nonetheless, Piaget’s analysis of play highlights why play is so enjoyable and how it mirrors cognitive development stages. It remains influential in how we understand different forms of play behavior in children.

Criticisms and Contemporary Applications of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget’s theory has had enduring influence, but it has also faced substantial criticism and has been refined by subsequent research. Here we discuss the main strengths and weaknesses of Piaget’s framework, and how modern findings have built on or challenged his ideas, as well as how Piaget’s theory is applied today.

Strengths and Contributions

Piaget’s theory was groundbreaking in recognizing that children think differently from adults. He was the first to systematically chart cognitive development, showing that infants, preschoolers, and older children have qualitatively distinct ways of reasoning. His stage model provided a useful roadmap of typical development that has helped parents, teachers, and psychologists understand what kinds of thinking to expect at various ages. Piaget also introduced key concepts – like schemas, object permanence, egocentrism, and conservation – that have become standard vocabulary in psychology and education. His work inspired thousands of studies; in essence, Piaget asked new questions about how children think, launching the modern science of cognitive development.

Additionally, Piaget’s view of children as active, self-motivated learners was a positive shift from earlier views of children as passive recipients of training. This has influenced educational philosophy: many early childhood and primary education programs incorporate Piagetian ideas, emphasising hands-on exploration, discovery learning, and adapting teaching to the child’s developmental level. The concept of not pushing a child beyond their “readiness” has its roots in Piaget’s work. Finally, Piaget’s theory, though proposed nearly a century ago, has proven robust in many respects – for example, the sequence of developmental milestones he identified (such as understanding object permanence before conservation, or concrete logic before abstract logic) has been broadly confirmed across cultures, even if the exact ages can vary.

Key Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory

Despite its contributions, researchers have raised several criticisms of Piaget’s theory:

Underestimation of Children’s Abilities

Piaget tended to underestimate what young children (especially infants and preschoolers) are capable of, in part because of the methods he used. His tasks often required children to perform certain actions or verbally explain concepts, which could mask competence if a child misunderstood instructions or lacked the motor skills. Subsequent studies using different techniques suggest that many cognitive abilities emerge earlier than Piaget reported.

For example, as mentioned, researchers like Renée Baillargeon demonstrated object permanence in infants as young as 3.5 to 5 months using visual tracking methods. However, Piaget thought it developed around 8–12 months.

Similarly, simpler versions of the perspective-taking task (such as using familiar objects or less complex displays) have shown that some 4-year-olds can take another’s perspective, suggesting Piaget’s three-mountains task was overly demanding. Thus, critics argue Piaget underestimated infants and young children – they may understand more than they can express or demonstrate in Piaget’s original experiments.

Overestimation of Adolescents and Adults

Conversely, Piaget may have overestimated the attainment of his highest stage. He suggested that by around 11-12 years old, given normal experience, everyone should develop formal operational thinking. However, research has found that many adolescents (and even adults) do not consistently use formal abstract logic, especially in domains where they have little experience. In fact, on Piaget’s own formal reasoning tasks (like the pendulum problem), a significant proportion of teenagers fail to show the hypothesised level of reasoning. It appears that advanced reasoning is often domain-specific – we think abstractly about topics we’re trained in or familiar with but may reason more concretely about other topics.

Therefore, the universality of formal operations has been questioned. Some psychologists have proposed additional stages or forms of thinking beyond Piaget’s fourth stage (e.g. post-formal thinking, which might include relativistic and dialectical thinking in adulthood), but these are not part of Piaget’s original theory.

Problems with Stage Theory (Continuity and Variability)

Piaget’s concept of stages – with broad shifts that apply across all domains of thinking – has been criticised for not capturing the true variability of cognitive development. Developmental research shows that children’s skills can be uneven: a child might show more advanced reasoning in one domain (say, social reasoning) than in another (like spatial reasoning), which violates the idea of a uniform stage of development.

Indeed, Piaget’s notion of stages as holistic structures has been challenged. Many now view cognitive development as more gradual and continuous than Piaget’s discrete stages. Abilities may develop in a piecemeal fashion, and minor experience or training can sometimes improve performance on Piagetian tasks (something that a strict stage view would not predict). Children might also revert to simpler thinking in some situations and use advanced thinking in others, rather than consistently operating at one stage. Thus, the stage model is seen by some as a useful approximation but not literally true in all details.

Limited Role of Social/Cultural Factors

Piaget has been criticised for downplaying the influence of social context and culture on cognitive development. His research was largely based on European children (often his own or those in Geneva), and he tended to emphasize universal processes of development. While he did acknowledge that social interactions and teaching could affect the rate of development, these were not central to his theory.

Critics point out that cognitive development can be significantly shaped by cultural practices – for instance, children who grow up in traditional societies that train specific skills (like navigation or weaving) can show advanced reasoning in those domains earlier than Piaget’s timetable. Vygotsky and his followers showed that instruction and language can accelerate or shape cognitive growth. Piaget’s tasks themselves when used in non-Western cultures, sometimes yield different results depending on familiarity and schooling. In short, Piaget’s theory underemphasises cultural variability and the contribution of social guidance, making it less comprehensive in explaining human cognition across diverse environments.

Methodological Criticisms

Piaget’s findings were based on relatively small, non-standardised samples – famously, some of his insights (like the sensorimotor substages) came from observing his own three children. He used flexible observational methods and clinical interviews rather than large experiments with statistical analysis. Later scientists have pointed out that this approach can introduce bias and makes it hard to replicate results. Piaget seldom reported detailed statistics, and some of his tasks might have unintentionally cued children in ways he didn’t account for.

That said, many of his qualitative observations have stood the test of time, but the lack of rigorous methodology means his age norms were not precise. Today’s researchers use more controlled experiments and larger samples to test developmental hypotheses, and this more rigorous approach has refined some of Piaget’s claims (often finding children’s competencies to be earlier or more context-dependent than he proposed).

Abstract Concepts and Explanatory Power

Some scholars have argued that Piaget’s theory, while describing what changes in children’s thinking, was less clear on why these changes occur. His concepts like “equilibration” or “operational structure” can be somewhat abstract. Critics say that beyond describing children’s behaviors at different ages, the theory doesn’t always provide a concrete mechanism for cognitive change (aside from maturation plus general experience).

For instance, why exactly do children move from preoperational to concrete operational thinking? Piaget’s answer of “brain maturation and self-regulation through equilibration” is seen as too broad. As one critique put it, Piaget’s theory is an “elaborate description of cognitive development that has limited explanatory power.” In response, later researchers developed more specific mechanisms (for example, information-processing accounts attribute changes to increasing working memory capacity, improved attentional control, etc., rather than a broad shift in stage).

Despite these criticisms, it’s important to note that Piaget’s core insights (that children actively construct knowledge and go through developmental changes in thinking) remain valid. Researchers have built on Piaget’s foundation rather than discarding it entirely, leading to more nuanced theories.

Contemporary Developments and Applications

Modern research in developmental psychology has extended Piaget’s legacy in several ways:

Neo-Piagetian Theories

Some psychologists (neo-Piagetians) integrate Piaget’s stage theory with more modern understandings of cognition, such as information-processing models. For example, Robbie Case and colleagues proposed that changes in children’s thinking with age can be explained by increases in working memory capacity and efficiency, which occur with brain maturation. They maintain the idea of stages or levels, but attribute the transitions to quantitative growth in processing power and domain-specific knowledge, rather than broad structural transformation alone. This helps address why a child might show uneven performance across different tasks (they may have more practice or knowledge in one domain than another). Neo-Piagetian models thus preserve Piaget’s sequence of developmental milestones but offer a clearer mechanism (cognitive capacity gains) for them.

Core Knowledge and Nativist Findings

On the flip side, some contemporary researchers (like Elizabeth Spelke, Alison Gopnik, and others) have found evidence that infants possess some innate cognitive capabilities – a notion that challenges Piaget’s view of the infant mind as starting from near zero and gradually building up. Studies using looking-time measures suggest that infants have early concepts of physics (objects can’t pass through one another, as Baillargeon’s studies showed), basic math (distinguishing quantities), and even morality (preferring “helper” characters to “hinderers” in simple scenarios). These “core knowledge” theories argue that evolution has endowed babies with a head start in understanding certain key domains, which Piaget may have overlooked by using tasks that underestimated infants. This doesn’t directly refute Piaget’s stages but indicates that some cognitive structures are present much earlier in an implicit form.

Social and Cultural Perspectives

Vygotsky’s work, which gained wider recognition in the West later in the 20th century, has complemented Piaget’s by highlighting the role of culture and teaching. Today, developmental psychologists often adopt a more interactionist view: both the child’s own explorations and social inputs shape development. For example, language development (which Piaget saw largely as a reflection of cognitive stage) is now studied as both a cognitive and a social phenomenon, where social interaction is crucial for children to acquire and refine language. Cross-cultural studies have enriched our understanding, revealing that Piaget’s stages may unfold in the same order universally, but the age range can vary and the skills emphasized can differ. In terms of applications, this means educators adapt Piaget’s ideas to local contexts – for instance, using familiar examples when teaching conservation to make sure children aren’t confused by the materials rather than the concept.

Educational Practices

Piaget’s influence on education remains strong, especially in early childhood education. Concepts such as “discovery learning,” “sensory play,” and “developmentally appropriate practice” owe their roots to Piagetian theory. Classrooms inspired by Piaget often feature hands-on activities where children manipulate materials (water tables, building blocks, science experiments) to learn concepts like volume, number, or cause-and-effect by themselves. Teachers assess a child’s stage of thinking and tailor activities accordingly.

For example, using concrete objects and visual aids when teaching 6-year-olds (who are mostly concrete operational and not ready for purely abstract lectures). The idea of not introducing certain abstract concepts until the child seems ready is also applied (though this is balanced with gentle scaffolding if using Vygotskian approaches). Piaget’s work on moral reasoning (he studied how children understand rules and justice) has also influenced character education, emphasising that younger children see rules as fixed and sacred, whereas older ones understand mutual agreements – guiding how adults discuss rules or discipline with different ages. While modern curricula integrate many other theories as well, Piaget’s legacy is seen in the learner-centered, activity-rich, and stage-aware strategies used in many schools.

Continued Relevance in Cognitive Science

Even in fields like cognitive neuroscience, Piaget’s ideas resonate. Researchers studying brain development have found parallels to Piaget’s stages – for instance, the prefrontal cortex (involved in planning and hypothetical thinking) matures considerably during adolescence, which dovetails with the emergence of formal operational skills. Some scientists suggest that Piaget intuited from behavior changes what neural development underlies: early sensorimotor intelligence correlates with sensorimotor brain regions, and the adolescent brain’s connectivity might underlie the new abstract abilities. Although Piaget did not know about neural networks, his stage descriptions sometimes anticipate the “timeline” of brain maturation that contemporary neuroscience confirms. Cognitive psychology has also explored topics Piaget raised, such as the nature of logical reasoning and problem-solving, albeit with more advanced methods. In sum, Piaget’s theory continues to inspire research questions, and elements of it have been incorporated into a more interdisciplinary understanding of development.

Summing Up Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development remains a cornerstone of developmental psychology. While we now recognise it isn’t a perfect or complete account, it was a monumental step in acknowledging the active, constructive mind of the child. The theory’s strengths include its broad developmental perspective and rich observational insights, and its weaknesses involve underestimating sociocultural factors and certain competencies. Modern research has refined the timeline and mechanisms of cognitive development but has largely validated the sequence Piaget outlined. In practical terms, Piaget’s ideas have encouraged educational systems to respect developmental stages and to let children learn through doing. As our understanding of child development grows, Piaget’s influence endures – often updated, sometimes debated, but unmistakably foundational in the study of how humans come to know and understand the world.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Q: What are the 4 stages of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development?

A: Piaget outlined four stages that children pass through:

- The Sensorimotor stage (birth to ~2 years), where intelligence is practised through sensory and motor interactions and object permanence is acquired;

- The Preoperational stage (about 2 to 7 years) is marked by the development of symbolic thought (language, pretend play). However, thinking is egocentric and lacks logical operations (children in this stage struggle with concepts like conservation);

- The Concrete Operational stage (about 7 to 11 years), when children become capable of logical reasoning about concrete objects and events, master conservation and classification, and overcome egocentrism;

- Finally, The Formal Operational stage (around 11 years onward), where adolescents and adults can think abstractly, reason hypothetically, and use deductive logic.

These stages always occur in the same order, although the exact ages can vary by individual.

Q: What is the difference between assimilation and accommodation in Piaget’s theory?

A: Assimilation and accommodation are two complementary processes of adaptation in Piaget’s theory. Assimilation means incorporating new experiences into existing schemas (mental frameworks). The child interprets something new in terms of what they already know. For example, a toddler who knows the schema “dog” might call any four-legged animal a dog – they are assimilating the new animal to their existing concept. Accommodation means adjusting one’s schemas to the new information – changing one’s understanding to incorporate the new experience properly. Using the same example, when the toddler learns that a cat is not a dog, they will modify their animal schemas (perhaps forming a new schema for “cat” or refining “dog” to be more specific). In short, assimilation fits new information into old ideas, while accommodation changes old ideas to fit new information. Both work together to drive cognitive development by keeping the child’s understanding in balance with experience.

Q: Why did Piaget believe children’s play is important for cognitive development?

A: Piaget saw play, especially pretend play, as an expression of the child’s developing mental abilities. In his view, play is dominated by assimilation – the child imposes their existing understanding on events for fun.

For instance, when a child pretends a broom is a horse, they are assimilating that object into their schema of “horse riding” without needing to accommodate to the broom’s real function. Piaget identified stages of play (practice play in infancy, symbolic play in early childhood, and games with rules in later childhood) that parallel cognitive stages. He believed play allows children to practice what they have recently learned in a pleasurable way, reinforcing their schemas.

However, Piaget did not argue that play by itself causes new cognitive development (he thought learning comes from real experiences and problem-solving). Rather, play reflects cognitive development – for example, the emergence of pretend play signals the ability to use symbols (a cognitive milestone of the preoperational stage). So, play is important as a symptom and support of cognitive growth, but in Piaget’s theory it’s not typically a driver of new stages.

Q: How does Piaget’s theory apply to education today?

A: Piaget’s theory has significantly influenced educational practices. Teachers often use the idea of developmental stages to guide curriculum – for example, using concrete objects and visual aids for primary school children who are mostly concrete operational thinkers, and introducing abstract concepts more in secondary school when formal operational thinking becomes more common. The concept of “readiness” suggests not pushing children to learn skills too early (e.g. not expecting a 3-year-old to understand algebraic logic).

Piaget also championed discovery learning: classrooms inspired by Piaget encourage hands-on exploration, where children learn by doing experiments, manipulating materials, and discovering principles themselves (with the teacher facilitating rather than directly instructing). For instance, to teach the concept of conservation, a teacher might set up a water play activity with different containers and ask students to predict and observe, rather than just telling them the answer.

Furthermore, Piagetian ideas support differentiation – adjusting tasks to the child’s developmental level. If a child is in the preoperational stage, educators use more stories, play, and examples tied to personal experiences. In summary, Piaget’s influence is seen in child-centered, active learning approaches and in structuring learning content in a developmentally appropriate sequence.

Q: What are some criticisms of Piaget’s theory?

A: Common criticisms of Piaget’s theory include:

- Underestimating young children – later research showed infants and toddlers have more cognitive abilities (e.g. some grasp of object permanence, number, etc.) than Piaget reported, often because his tasks were too difficult or reliant on motor skills.

- Overestimating universality of stages – not all people reach formal operations, and cognitive development is more uneven and continuous than strict stage definitions imply. Children might solve a problem in a “higher stage” way in one context but not in another, suggesting flexibility that Piaget’s stages don’t account for.

- Insufficient attention to social and cultural factors – Piaget largely focused on the individual child, but social influences (parents, peers, language) and culture can significantly affect cognitive development (a point emphasised by Vygotsky and others)

- Methodological issues – Piaget’s research was based on small samples and observational methods, so some findings lack rigorous statistical support. Despite these criticisms, Piaget’s theory is still valued for its insightful observations and has been updated, rather than discarded, by modern psychologists.

References (Harvard style)

- Bjorklund, D.F. (2018). A Metatheory for Cognitive Development (or “Piaget is Dead” Revisited). Child Development, 89(6), 2288-2302. (Discusses modern perspectives on Piaget’s theory).

- Inhelder, B. & Piaget, J. (1958). The Growth of Logical Thinking from Childhood to Adolescence. New York: Basic Books. (Classic study on formal operations and the pendulum problem).

- Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International Universities Press. (Piaget’s work on Sensorimotor stage and object permanence, based on his observations of infants).

- Piaget, J. (1962). Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood. New York: Norton. (Piaget’s analysis of play and its role in development, introducing types of play corresponding to cognitive stages).

- Scott, H.K. & Cogburn, M. (2023). Piaget. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. (An updated overview of Piaget’s theory for clinicians).

- Sanghvi, P. (2020). Piaget’s theory of cognitive development: a review. Indian Journal of Mental Health, 7(2), 90-95. (Reviews Piaget’s stages, key concepts, criticisms, and educational implications).

- Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Vygotsky’s work – often contrasted with Piaget’s – emphasises social context and the Zone of Proximal Development).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: