Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to identify the impact that teenage unemployment numbers have on the unemployment rate in America. The inclusion of the working age teenage population in the calculations distort the true amount of participation representation within the nation’s the labor force. Unstable variables such as the fluctuations in work force involvement caused by educational institution requirements and lack of integration into the labor market as a whole pose threats to the formula by which our unemployment rate is calculated. These discrepancies are further exacerbated by the disregard for non-participants in the workforce, therefore causing misinformation among the American people, and contribute to the overall misallocation of government efforts.

Get Help With Your Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional essay writing service is here to help!

In an ever-changing economy, unemployment is a major factor that many Americans face. While we are currently experiencing some of the lowest rates of unemployment that the country has ever seen, it is important that we know the truth behind those numbers. According to Krugman and Wells, unemployment is defined as “the number of people that are actively looking for work but aren’t currently employed” (Krugman & Wells, 2015). Defining unemployment in this manner excludes the number of Americans that are considered “discouraged workers” that have stopped looking for work due to job market availability or “underemployed workers” who currently hold part time jobs since they can’t find a full-time job. After all, the unemployment rate is determined by calculating the overall percentage of people who are currently employed compared to those that are unemployed. With this information, it is plain to see how the unemployment rate can provide an inaccurate account of the true number of unemployed Americans.

In order to better understand the concept of unemployment, it is important to know that there are three different types: structural, frictional, and cyclical. Structural unemployment exists when there are more people looking for jobs than there are available jobs, frictional unemployment occurs based on the time a worker spends looking for a job, and cyclical unemployment occurs when there are changes in the actual and natural rates of unemployment (Krugman & Wells, 2015).

Discussion

When dealing with the idea of teenage unemployment, I found it hard to categorize the type of unemployment that this population falls into. Discouraged workers are those that are no longer looking for work, which is what seemed most feasible to me in this instance since majority of students who once held a job are unemployed due to the recurring commencement of the school year. Upon further research, I found that cyclical unemployment is the category teenage unemployment actually falls into since companies tend to hire people with more experience as a natural employment variable. While some teenagers of working age obtain summer jobs that must be ended prior to the schoolyear, in actuality, most working age teenagers that do not have a job have simply not started their search in the labor force at all. I am presented with the question of how teenage unemployment falls into an unemployment category at all when majority of working age teenagers haven’t searched for work at all to begin with.

In America, at any given time, there are approximately 17 million teenagers attending high school (Davis & Bauman, 2013). For starters, unemployment among teenagers is overstated because we fail to take into consideration the fact that their primary “job” for nine months out of the year is to attend school and obtain an education. When conducting unemployment calculations, Krugman and Wells address the working age as 16 years and older (Krugman & Wells, 2015). While 16 years old is the minimum age requirement to legally obtain a job, many teenagers at that age are solely attending school. Teenagers in the working age group are required by law to attend school up until they graduate or reach 18, unless they have their parent’s consent to discontinue their education before the age of 18 (“School Leaving Age,” 2019). With the statistics from the United States Census Bureau, there were 42,225 high school students that had to repeat their previous year of education, and only 2,761 of those students dropped out of high school between the ages of 15 and 24 (Davis & Bauman, 2013). With this information, we can see that only a tiny fraction of students of working age choose to discontinue their high school careers and are forced to join the labor force. Therefore, the millions of American teenagers in high school have the option as to whether they will start their adventure in the labor force or focus their efforts solely on their education. This proves to be an important factor that should be considered when including the 16 to 18-year-old population count as part of the unemployment rate calculation.

Of the millions of working age teenagers pursuing their education, 79.9 percent of teenagers attending school partake in high school extracurricular activities (O’Brien & Rollefson, 1995). According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the correlation between extracurricular activities and better attendance and better educational performance is clear based on the data that we have, however, it is also stressed that we cannot heavily rely on this evidence due to the lack of professional, structured studies. From society’s continued observations, participation in school associated activities are obviously detrimental because it teaches students the importance of time management skills as well as how to function in social settings and interactions authority figures. Overall, involvement in these activities builds the necessary skills required to maintain a stable job and truly emphasize the importance of reliability and accountability altogether. A working age student’s ability to attend school and partake in extracurricular activities leaves minimal, if any, time to pursue a job outside obtaining an education during the school year. These factors are important when considering the practicality of teenage labor force efforts, and how their extracurricular activity involvement has the potential to positively affect their future employment opportunities as well as aid in combating high unemployment numbers in the American economy.

Underemployment

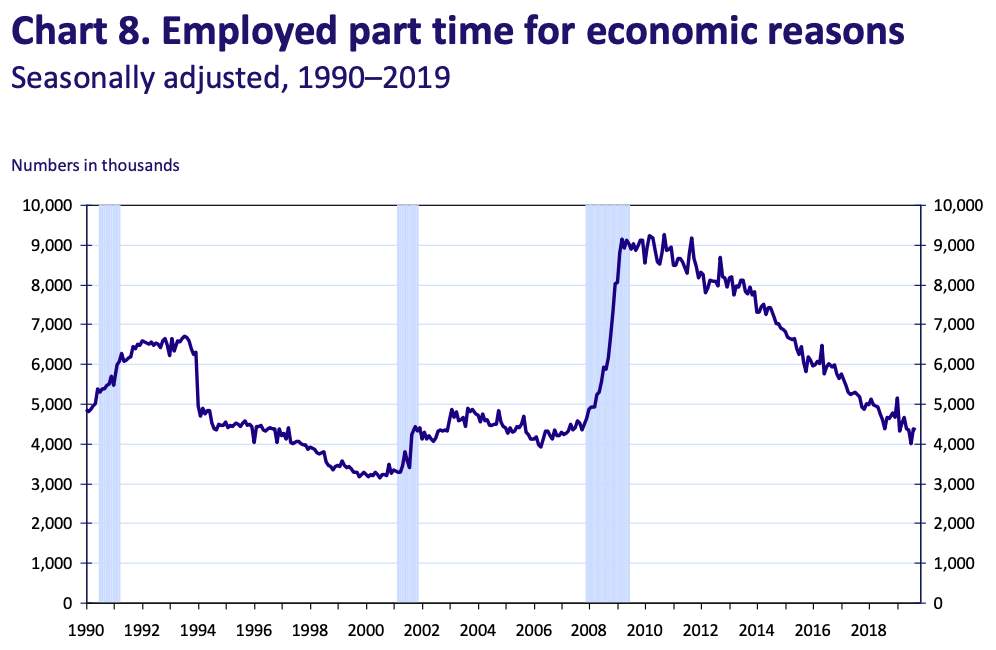

Underemployment is a major contributor to the unemployment scenario. These numbers are not taken into consideration when calculating the national unemployment rate. Underemployment consists of the part-time workers that have obtained a job in order to meet their economic needs until they can find full time work. The graphs below, figures one and two, display the number of unemployed teenagers and adults, and the number of the aforementioned populations holding part time positions as well. According to the United Health Foundation, 8.5 percent of Americans are underemployed (“Underemployment Rate,” 2019). Only 32 percent of the entire working age student population hold a job during the school year, which is a miniscule fraction of the total number of employed Americans in our economy (“Unemployed teens,”2019). This number changes significantly during summer months. According to the 2019 census findings, the number of employed youths has risen by 2.4 million members of the 16 to 24-year-old population during the summer months (“Employment and Unemployment,” 2019). The overall youth participation in the labor force during summer months of 2019 was at 61.8 percent, providing the lowest unemployment rate, of 9.1 percent, among teenagers since 1966 (“Employment and Unemployment,” 2019). While these numbers might seem to have a major impact on the overall unemployment rate, it is important to remember that the increase that we see during summer months is due to student availability to work outside of their requirements within the education system. It is important that we realize the fact that these numbers will decrease significantly during the school year and leave the unemployment rate with extremely overestimated figures.

As previously stated, underemployed Americans, or part-time employees, are not counted in the unemployment rate calculations at all. For underemployed adults holding part time positions, it is important to understand that they are still receiving income and therefore do not meet the unemployment standard. However, students who hold part time positions are considered employed, and when they end their employment to return to the educational system, the unemployment numbers increase significantly. Figures one and two below consist of two graphs that reiterate the fact that students under the age of 18 should not be included in the unemployment rate calculations at all. The frequent increases and decreases seen in the teenage employment trends shown in figure one displays the differences in consistent working availability between the teenage and adult populations. The substantial increase in student unemployment at the beginning of the school year negatively impacts the fluctuation of the unemployment rate, and dramatically distorts the calculated unemployment statistics as a whole.

Figure 1: Unemployment Rates for Teens (16-19yrs), Men (20+yrs), and Women(20+yrs)

(U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019).

Figure 2: Part-time Employed Americans.

(U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019).

Unemployment Benefits

Unemployment benefits are also a factor when considering who to include in the unemployment rate calculations. When a person is considered unemployed, through no fault of their own, they have the opportunity to apply to receive unemployment insurance benefits while they seek further employment opportunities.

While part-time workers do not qualify for these benefits in most states, some students may be afforded the opportunity to apply and receive these benefits. As unemployed members of society, certain states allow students to acquire unemployment insurance for up to 26 weeks, as long as they are actively searching for employment (“Policy Basics,” 2018). With that being the case, this is often beneficial to college age students, who might fall into the 18 to 19-year-old gap, who choose to take night classes. Their age constitutes them as “working age teenagers”, but as college students, they are allotted the flexibility of scheduling their classes around a full-time job throughout the year. The night class schedule enables them to have the ability to maintain a full-time job, while still allotting them the time to pursue their higher education goals. If they are able to obtain a full-time position, they may qualify for unemployment insurance benefits.

Find Out How UKEssays.com Can Help You!

Our academic experts are ready and waiting to assist with any writing project you may have. From simple essay plans, through to full dissertations, you can guarantee we have a service perfectly matched to your needs.

View our academic writing services

For teenage high school students who are seeking to qualify for unemployment benefits, there tend to be more obstacles, as there should be. In many American states, high school students are disqualified from receiving these types of benefits due to their educational institution’s hours. In order to obtain unemployment benefits, students would have to be able to work a full-time job, which is typically during the day. In many cases, this would disqualify most high school students. However, there are select states that allow students to receive benefits regardless of their education obligations, as long as they are actively seeking employment and available for full-time employment, potentially after school hours (Whittaker & Eder, 2012). This type of flexibility within the unemployment insurance benefits system leads to further skewed numbers, and potential abuse, as students may seek termination from their summer employment in order to qualify for these monetary benefits.

True Costs

The bottom line when it comes to unemployment is the fact that there is more at stake for our nation than just considering the fluctuation of the unemployment rate. As for myself, I always thought that the lower the number, the better the economic status. While this is true, there certainly is more to the concept than I had considered. For instance, the loss of tax revenue on a national scale has an impact of our total economic status. While unemployed members of society receiving unemployment insurance benefits will pay federal taxes on their “income”, it still isn’t the amount of taxes that would be paid on an entire paycheck if they were working a full-time job. Obviously, the unemployment insurance is there in order to make sure Americans can meet their basic needs, so the monetary compensation isn’t a large sum of money, so we can only anticipate a lower amount of taxes being brought forth by those receiving the benefits as a whole. This depletes the funding that the government has set aside for this program, and it causes losses in the revenue total, thus placing the government financial status in a less than ideal position. This has the potential to cause our government to borrow more money and further exacerbate the financial strain. Additionally, there is a lack of utilization of our resources that really takes a toll on the economy. When there aren’t enough people to aid in the distribution of products and services, the export business suffers as well. Again, this places strain on the economic status. And again, we have to remember that sometimes there are jobs available, but the discouraged workers aren’t looking anymore. Since they aren’t counted in the unemployment rate, the impact that they have on our economy isn’t always measured accurately. Once these workers started searching for work again, they face the risk of being overlooked by employers since their discouragement tends to cause a large gap in employed time periods, which can be a red flag to some employers. This poses further discouragement and almost alienates the people searching for work. It is a cycle, but the more we educate our fellow American on the issue, the better chance we have to make changes and really set our nation, and our people, up for success.

Calculation Inclusion As the numbers of unemployed Americans shifts frequently, the numbers have significant potential to be miscalculated with the inclusion of unemployed teenagers. The different factors that pertain to their circumstances, from the sporadic summer employment opportunities, to their ability to potentially quality for monetary benefits from unemployment insurance, there are too many unstable variables to include the teenage working age group in the unemployment rate calculation.

As of August 2013, the unemployment rate was missing approximately five million workers (Shierholz, 2013). The official unemployment rate was 7.3 percent, however, if the unemployment rate was calculated using the true number of Americans out of work, the number would have increase to 10.1 percent (Shierholz, 2013). The current calculation does not include the number of non-participants in the economy, which means those that are not currently seeking work. Again, if this significant difference is one to be overlooked for the sake of an accurate account of active members of the labor market, the same should go for the student population who leave the work force to go back to school. Without the number of teenagers included into the equation, the numbers would differ greatly. If these numbers were reversed, and the adults who are not currently seeking work were included in the number and left the teenage age group out of the equation, the number would reflect a more accurate depiction of the national unemployment rate, thus helping the government and other entities to find prospective solutions to a serious, ongoing issue in the American economy today.

Conclusion Though there are many factors that play a role in our nation’s unemployment situation, there are changes we could make that have the potential to positively impact our economic standing. From removing the inclusion of high school working age students in the unemployment rate calculations to the inclusion of discouraged workers in the formula, we could obtain a more accurate representation of our economic standing. The way that this information is handled now often leads to miscalculated proportions, and therefore, misinforms the American people altogether. The more we support one another and educate our youth on the matter, the better chance we have to decrease our unemployment rate as a whole. If we modify the way we calculate the unemployment rate by removing the high-school age workers, the American people will have a better awareness of the true cost of unemployment and obtain the ability to implement valuable changes in our economy.

References

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2018, December 3). Policy basics: unemployment insurance. Retrieved October 25, 2019, from https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/policy-basics-unemployment-insurance

- Child Trends. (2018). Youth employment. Retrieved October 17, 2019, from https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/youth-employment

- Davis, J. & Bauman, K. (2013, September). School enrollment in the United States: 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2019, from https://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p20-571.pdf

- Glavin, C. (2014, February 6). School leaving age. Retrieved October 17, 2019, from https://www.k12academics.com/dropping-out/school-leaving-age

- Kids Count. (2019, October). Unemployed teens age 16 to 19: kids count data center. (2019, October). Retrieved October 18, 2019, from https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/5051-unemployed-teens-age-;16-to19?loc=1&loct=1#detailed/1/any/false/37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133,38/any/11461,11462

- Krugman, P., & Wells, R. (2015). Economics (4th ed.) New York, NY: Macmillan Education.

- Pettinger, T. (2019). Economics cost of unemployment. Retrieved October 25, 2019, from https://www.economicshelp.org/macroeconomics/unemployment/costs/

- Shierholz, H. (2013, October 13). The “true” unemployment rate is the one BLS releases every month*, but it’s not the one “true” measure of labor market slack. Retrieved October 22, 2019, from https://www.epi.org/blog/true-unemployment-rate-bls-releases-month/

- Sweet, R. (1982.) Hidden unemployment among teenagers: a comparison of in-school and out-of-school indicators. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv:32844

- United Health Foundation. (2019). Underemployment rate. Retrieved October 17, 2019, from https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/Underemployed/state/ALL

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019, October 4). Charting the labor market: data from the current population survey (CPS). Retrieved October 16, 2019, from https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cps_charts.pdf

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019, October 24). Labor force characteristics. Retrieved October 25, 2019, from https://www.bls.gov/cps/lfcharacteristics.htm

- US Census Bureau. (2014, December 9). Nearly 6 out of 10 children participate in extracurricular activities. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2014/cb14-224.html

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019, October 4). Table A-16. Persons not in the labor force and multiple jobholders by sex, not seasonally adjusted. Retrieved October 17, 2019, from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t16.htm

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019, October 4). The employment situation- September 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2019, from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

- Whittaker, J. M., & Eder, A. (2012, September 7). Unemployment compensation (UC): eligibility for students under state and federal laws. Retrieved October 18, 2019, from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42707.pdf

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: