Introduction

The aim of this paper is to reflect on strategies to combat low level disruption in the classroom. Tackling minor discretions in acceptable behaviour can amount to a large percentage of teaching time lost in a lesson. During this lost time all students in class have missed valuable learning opportunities, not just the ones that needed to be challenged. It can also disrupt well laid out plans for the lesson. The setting of “high expectations which inspire, motivate and challenge pupils” is widely believed to be imperative as such it is part of the teaching standards (S1). The balance between enthusiasm and orderly behaviour is difficult to achieve. Lively discussion and engagement leads to deeper understanding in the topic being covered and allows better knowledge retention as shown in Dale’s Cone of Experience (Dale, 1946). Lower down the cone represents greater knowledge retention and involves the learner experiencing the subject or topic rather than just being shown.

Dale’s Cone of Experience (Dale, 1946, p. 107)

Personally, I want to replicate, in the students, the joy I possess in the subject and have total control of the behaviour. It is a tall order but high expectations are applicable to both student and teacher. There are strategies that promise to achieve this ideal situation in theory and I will reflect on some of these in practice using the Jay & Johnson model (Jay & Johnson, 2002). This model has three parts, description, comparison and critique in that order. The setting for this reflection is a school that achieves on or a little below national average with a Progress 8 score of -0.17 and an Attainment 8 score of 40.7 against an average of 44.6 for England. In the last Ofsted report (Ofsted, 2017) the school was rated as requires improvement (3) and one of the key findings was that occasionally, some teachers’ expectations of pupils’ behaviour are still not high enough. It is non-selective and is in an area with more selective schools than average. Two thirds, approximately, of the students are classed as pupil premium. The behavioural framework, although still developing, is consistent and clear throughout the school. The class is the top tier ability within year 7 minus those labelled as gifted and talented. The ratio of male students to female students is about 2 to 1. The students are generally energetic, enthusiastic and bright as a group. Their behaviour is not probably considered challenging individually but as a group we suffer large amounts of lost learning time through low level disruption. The class demonstrates each and every feature of this behaviour, at a low level, as outlined in the report titled Below the radar: low-level disruption in the country’s classrooms (Ofsted, 2014) :

•talking unnecessarily or chatting

•calling out without permission

•being slow to start work or follow instructions

•showing a lack of respect for each other and staff

•not bringing the right equipment

•using mobile devices inappropriately

Description

The lesson started after a period of recess for the students. They did not all arrive together but those that were on time lined up outside the classroom door. However, this was not an orderly queue but more of a gathering partly due to the students but architecturally the classroom is position at the end of a corridor with no room for a straight line. Male students were still full of the energy they had brought with them from the school yard demonstrated by grabbing each other and almost wrestling right outside of the door. They were invited in and instructed to commence their starter booklet as is the routine. A few more students appeared less than a minute after the main cohort and it took longer than it should have for them all to settle down. After the starter the questioning part of the lesson commenced using hands up and picking from those actively engaged. There was some shouting out that needed to be challenged but even though it was challenged it continued to the point that one of the students needed to be removed from the classroom and spoken to outside. This happened throughout the lesson and in total 4 students needed removing and speaking to outside the classroom. I would estimate that 15 minutes, about a quarter of the lesson, was lost through low level disruption. Examples of the behaviour in this lesson was:

- Talking while the teacher or another student was talking

- Calling out without permission

- Not getting on task in timely fashion

- Playing paper, scissors & stone whilst the teacher’s back was turned

There are parallels in this list compared to the list provided in the ‘Below the Radar’ report listed above (Ofsted, 2014).

Although several behaviour management strategies in line with the school’s policies (X School, 2018) were used during the lesson more needed to be done to improve the quality of the lessons in the future. The report itself did not focus on strategies in the classroom bar the setting of high expectations and that the teaching staff do not shirk their responsibility for maintaining these. It took a more holistic viewpoint on school culture that also includes parents of pupils and the communicating of the high expectations to them as being the most important factor in maintaining this culture. This is backed up by research into school culture where a positive perception of the school is directly linked to higher levels of attainment and better behaviour throughout. (Brand, et al., 2003)

The school employs consultants for the management of behaviour to help create that culture following the publication “When the Adults Change, Everything Changes (Dix, 2017)”. However this has not been fully implemented yet.

After a ten minute detention to conduct a ‘build and repair meeting’ with the most disruptive students eight phone calls were made that evening to 8. All parents that were spoken to pledged their full support. Five students were put on a monitoring report grading the students’ behaviour each lesson to be taken home and be checked by parents every day. The remainder were put on notice that they would also be on report if behaviour didn’t improve. The high expectations were reiterated to both the students and their parents. Everyone involved in that child’s education were now aware of what was expected in terms of behaviour and now invested in the maintaining of the high expectations.

Find Out How UKEssays.com Can Help You!

Our academic experts are ready and waiting to assist with any writing project you may have. From simple essay plans, through to full dissertations, you can guarantee we have a service perfectly matched to your needs.

View our academic writing services

Overall behaviour of that class improved markedly. Two of the parents that were supposed to be contacted were not because their details on the school systems were incorrect. The corresponding students’ behaviour did not initially improve. But they fell in line with their peers as they are a greater developer of a good classroom culture than parents or teachers (Petty, 2006, p. 183). The reports were taken home by these students and were seen by the parents.

Critique

These improvements were not entirely permanent. The power of parents is not the whole answer as at this age adolescents are seeking independence of thought (Rogers, 2007, p. 81). They want to make their own choices. Research has shown developing empathy in students to make the right choices is a more influential tool (Barr & Higgins-D’Alessandro, 2007). The role of parents is not without use but the role of peers is a greater influence at this age in the students’ development. Boys are more susceptible to peer pressure than girls (Berndt, 1979). They will risk the chance of being reprimanded for their actions in order to feel the adulation from their peers. This class is majority male and is clearly susceptible to such risk-taking behaviour. Studies have shown this kind of male dominated behaviour can be fostered in competition especially in maths (Cárdenas, et al., 2014)Dreber, von Essen & Ranehill (2012). Introducing more rewards, games and competition could be a more useful tool with this class than trying to use policy, parents and punishments.

Conclusion

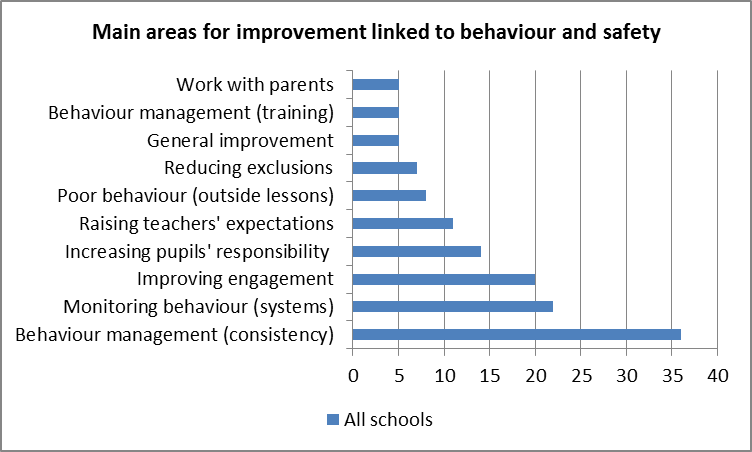

All strategies discussed above in behaviour management play a vital part in improving the learning of students. The importance of a scholarship culture inside the school and from the supporting community, parents and carers is undoubtably vital for the success. Research supports that what parents do, their style of parenting, is a direct positive influence on the intellectual, behavioural and emotional development of that next generation. (Ermisch, 2008). All things are not equal, and individuality brings more challenges that requires a bigger toolkit of strategies. The students are becoming individuals discovering their own paths away from the family home. Some come from single parent families, some from co-parenting situations or a whole range of scenarios. The level of influence is dramatically different and the consistency is unreliable. This brings me back to Below the Radar (Ofsted, 2014). The below shows analysis of areas for improvement relating to behaviour in 95 schools inspected between January and March 2014.

Consistency is the biggest area for improvement. We cannot enforce consistency outside of school as is the nature and diversity of life, but we can create that culture within the classroom and the school. This can be supported by parents in a whole school and community approach to a learning behaviour culture.

References

- Barr, J. J. & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A., 2007. Adolescent Empathy and Prosocial Behavior in the Multidimensional Context of School Culture. Journal of Genetic Psychology, Volume 168, pp. 231-250.

- Berndt, T. J., 1979. Developmental Changes in Conformity to Peers and Parents.. Developmental Psychology, 15(6), pp. 606-16.

- Brand, S. et al., 2003. Middle School Improvement and Reform: Development and Validation of a School-Level Assessment of Climate, Cultural Pluralism, and School Safety.. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(3), pp. 570-88.

- Cárdenas, J.-C., Dreber, A., von Essen, E. & Ranehill, E., 2014. Gender and Cooperation in Children: Experiments in Colombia and Sweden, s.l.: PLoS ONE.

- Dale, E., 1946. Audio-visual methods in teaching. 1st ed. London: Harrap.

- Dix, P., 2017. When the Adults Change Everything Changes. 1st ed. s.l.:Independent Thinking Press.

- Ermisch, J., 2008. Origins of Social Immobility and Inequality: Parenting and Early Child Development. National Institute Economic Review, Volume 205, pp. 62-71.

- Jay, J. K. & Johnson, K. L., 2002. Capturing Complexity: A Typology of Reflective Practice for Teacher Education.. Teaching and Teacher Education, Volume 18, p. 73–85.

- Ofsted, 2014. Below the radar: low-level disruption in the country’s classrooms, s.l.: Ofsted.

- Ofsted, 2017. Inspection Report X School, s.l.: Ofsted.

- Petty, G., 2006. Evidence-based Teaching: A Practical Approach. illustrated ed. s.l.:Nelson Thornes.

- Rogers, B., 2007. Behaviour Management: A Whole-School Approach. 2nd ed. s.l.:SAGE Publications.

- X School, 2018. Behaviour Policy and Statement of Behaviour Principles, s.l.: X School.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: